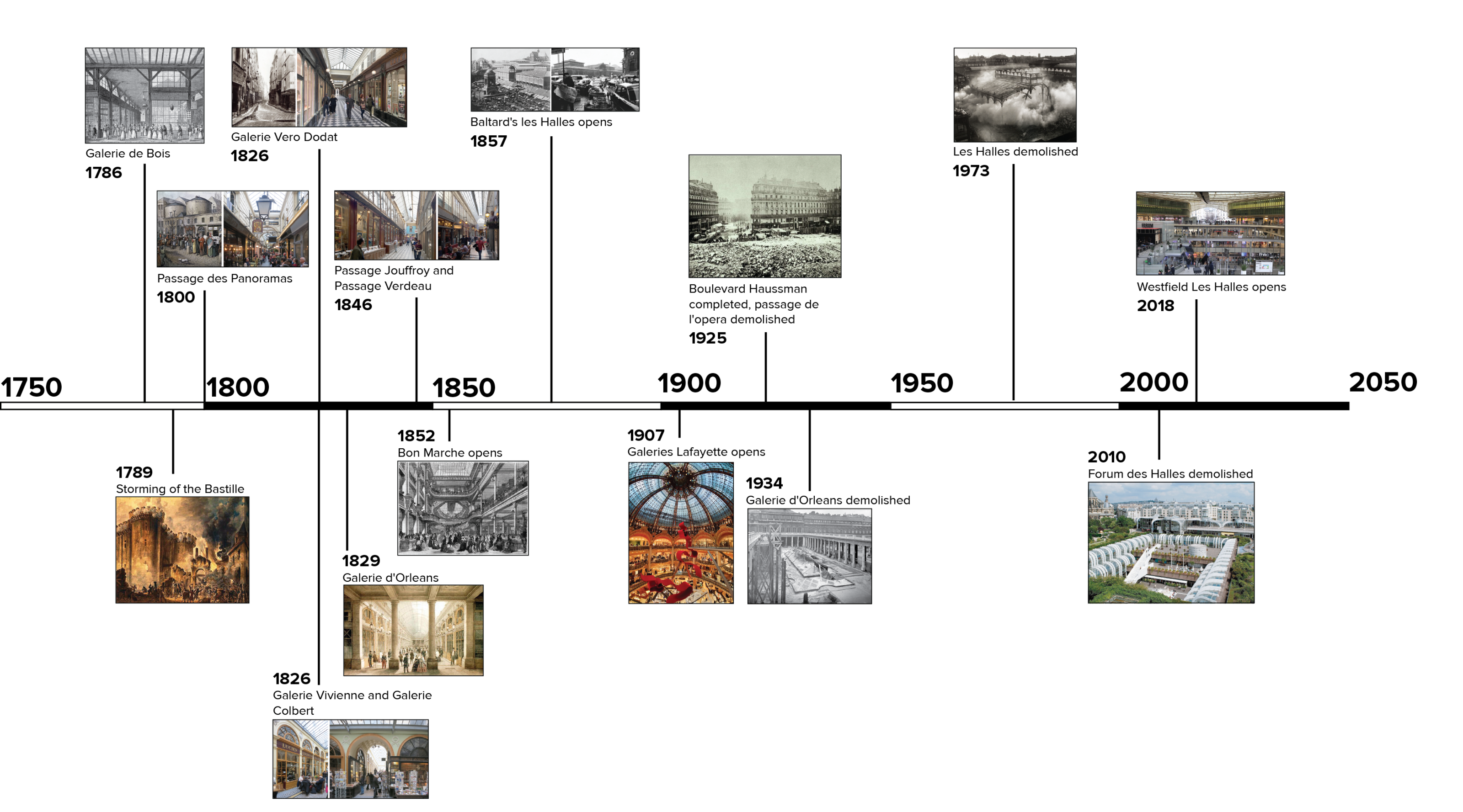

Shopping was born in Paris. It was the grand-child of two revolutions: the first was the overthrow of Louis XVI and the ancien régime, and the second was the use of the steam engine to power cotton mills, which ushered the industrial revolution in England and the continent. The French Revolution catalyzed the emergence of a new social class, the bourgeoisie, whose purchasing power largely displaced the pre-revolutionary system of aristocratic patronage of artisanal guilds and craftsmen. The Industrial Revolution led to the proliferation of commodities, products that depended on the play of market forces, including advertising and the attraction of investment capital. At the intersection of the social world of the bourgeoisie and the material world of commodities lay a new activity, one that we take for granted today: shopping.

Shopping is typically looked down upon as a frivolous and unenlightened middle-class activity (when walking into the just-then completed Pompidou Center in the 80's, designed to foster a broader public appreciation of modern art, the philosopher Jean Baudrillard dismissively accused it of enabling the consumption of art, and turning museum-goers into shoppers. This was not meant as a compliment). The story of the evolution of shopping is however more than just a chronicle of consumption: it is also a story of the settings that allowed the bourgeoisie to forge its identity, and to display its newly achieved status. As well as pleasure gardens, theaters, restaurants and cafés, these settings included the passage couvert (covered arcade), the boulevard and the grand magasin (department store). Cultural critic Walter Benjamin went as far to suggest that arcades were the birthplace of the modern era - a place where commodities and new building techniques came together to create a new social realm, one that embodied the collective material aspirations of the new middle class. Since status was now something to be achieved rather than inherited, status symbols (whether luxury goods or philanthropic endeavors) acquired growing prominence. This was also a time that saw the emergence of the flâneur - the discriminating urban wanderer who relished the never-ending panoramic spectacle of the city - and his counterpart the badaud - the gullible consumer of goods and experiences.

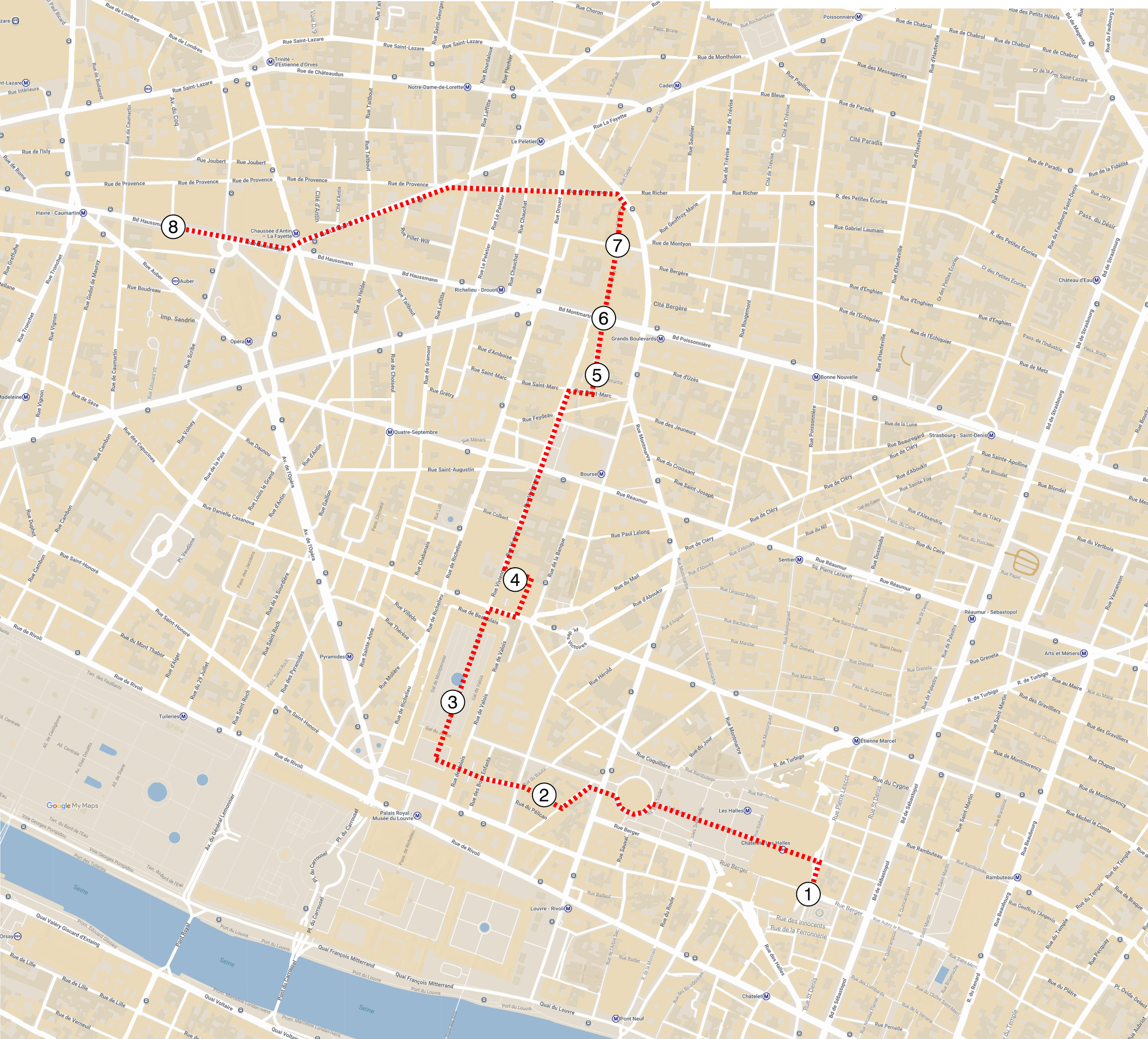

Our walk through this momentous period in history starts at Les Halles, the location of the original central market of Paris, and meanders through the nearby Palais Royal (which at the time of the revolution provided a counterpoint to the formalities of Versailles) and through five historical covered arcades, ending at the Galeries Lafayette on the Haussmann Boulevard. It is a walk-through time and space, one that follows the rise of the shopping arcades and their eventual demise. It is a journey through settings that inspired Parisian authors such as Honoré de Balzac, Emile Zola, Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin, authors who will help illuminate our wanderings.

1. Les Halles: the belly of Paris

Les Halles Market in its heyday, when it was the largest

market in the western world. On the left: the Fountain of the Innocents

is all that remains today of the old market and adjacent cemetery; on the

right: increasing congestion led to the relocation of the Le Halles market to

the Parisian suburb of Rungis; the subsequent demolition of the glass and

steel market pavilions in the 70's caused a huge outcry.

Les Halles Market in its heyday, when it was the largest

market in the western world. On the left: the Fountain of the Innocents

is all that remains today of the old market and adjacent cemetery; on the

right: increasing congestion led to the relocation of the Le Halles market to

the Parisian suburb of Rungis; the subsequent demolition of the glass and

steel market pavilions in the 70's caused a huge outcry.

The intersection of Rue Berger and Rue Pierre Lescot in Paris, located at the south east corner of the new "canopée" crowning the Westfield Forum des Halles shopping mall, is a fitting place to start this journey. This was where Paris' central market was established around the year 1100: we are standing at the crossroads of over 900 years of commercial activity. The Forum in its current incarnation represents the fourth major urban intervention in the neighborhood - it replaced a failing 80's mall, which in turn replaced the famous covered market of Les Halles, which in turn replaced the warren of streets where the original markets of Paris were located. The nearby Fountain of the Innocents stands as the only remnant of the historical burial ground originally located there, before being displaced at the time of the revolution to allow for the expansion of the ever-growing central market.

Les Halles is located in the exact center of Paris, and if you had been standing in this spot around the 1800's, a very different spectacle would have unfolded before your eyes, one featuring filthy and unpaved narrow streets with open sewers, strewn with rotten vegetables and splattered with blood from slaughtered animal carcasses. Butchers and charcutiers would have plied their trade in storefronts, and the stench from the slaughtered carcasses would have been overpowering for our delicate 21st Century noses - it was the stuff of a county health inspector's nightmare.

The story of urban design in many Western cities is in large part the story of cleansing the raw, working medieval city, and replacing the warren of streets with public spaces or structures glorifying the State. In Paris Henry IV started the trend by creating the Places Royales, the Place des Vosges and the Place Dauphine, the first of many royal squares n Paris. However at the dawn of the 19th Century, commerce itself was becoming celebrated, with the creation of grandiose civic public markets in numerous European Capitals - Covent Garden, Smithfield and Billingsgate in London, La Boqueria in Barcelona and of course the Les Halles market in Paris. The brainchild of Napoleon III, and immortalized in Emile Zola's novel, "The Belly of Paris", the vast brick and cast iron pavilions were completed by 1857 - perhaps France's answer to England's own Crystal Palace, completed a few years earlier, both monuments to new construction techniques. Les Halles was the biggest market in the western world, fed by a new railway network that could bring in produce overnight from all over France.

Access and circulation challenges eventually led to the relocation of Paris' central market to Rungis, south of Paris, in the 1960's - Rungis is still today the biggest wholesale market in the world. The famed pavilions were unceremoniously destroyed to huge public outcry, and a much-reviled underground shopping mall was built in their place - ironically a bit of a rabbit warren, not unlike the medieval streets that once stood there!

Westfield eventually took over the failing mall, demolished most of it and inaugurated the new "canopée" in 2016 - the latest step in the transformation of what used to be working market dedicated to the wholesale commerce into a shopping destination focused on discretionary purchase. Somewhere along the way, an activity that had not existed in pre revolutionary Paris needed to be invented; that activity was shopping. In order to understand how shopping came about, we need to head towards the nearby Galerie Vero Dodat.

2. Galerie Vero Dodat: a new kind of street

On the left: the scale of Rue Aumaire (photograph by Charles

Marville) was typical of most Parisian Streets prior to Haussman's

interventions. On the right: Galerie Vero-Dodat was a new kind of semi-public

street (author's photograph), offering a very different kind of experience.

On the left: the scale of Rue Aumaire (photograph by Charles

Marville) was typical of most Parisian Streets prior to Haussman's

interventions. On the right: Galerie Vero-Dodat was a new kind of semi-public

street (author's photograph), offering a very different kind of experience.

Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the short street leading to the Galerie Vero-Dodat, is representative of the scale and width of many Parisian streets before the large-scale interventions of Baron Haussman, Paris' very own nineteenth century Robert Moses. In these days it would have been unpaved, without sidewalks, and with an open sewer running down the middle. Building facades were generally solid at street level, with the occasional shop or workshop breaking the monotony. Horse drawn carriages would have been speeding through on their way to the Bourse or to the Rue de Rivoli, posing a danger to any pedestrian unlucky enough to be in the way. The streets of pre-revolutionary Paris were not a place conducive to leisurely strolling.

But take a right turn through the galerie's portal and you have entered a different world - gleaming surfaces, sophisticated flooring and delicately proportioned storefront vitrines greet your eye: a fairytale-like world featuring vitrine after vitrine displaying a proliferation of products and textile - a seemingly endless array of seductive goods. Built 20-odd years after the events of the French revolution, and anchored by les Halles and the Palais Royal, the Galerie Vero-Dodat (named after its developers, two wealthy charcutiers), was one of the first places in Paris to get gas lighting - and so one can imagine what it felt like to step out of from the chaos of the street into this artificially lit artificial street: it would have been like walking into an exquisite and magical cabinet of curiosities, filled with an enticing array of goods for sale. A place where one could linger, tip one's hat to fellow shoppers, and appreciate the selection of goods on hand. This was a new kind of leisurely activity, far removed from the utilitarian commerce taking place at Les Halles. Cultural critic Walter Benjamin describes how the arcades allowed for the emergence of this new urban type: "Before Haussmann wide pavements were rare, and the narrow ones afforded little protection from vehicles. Strolling could hardly have assumed the importance it did without the arcades. ‘The arcades, a rather recent invention of industrial luxury,’ so says an illustrated guide to Paris of 1852, ‘are glass-covered, marble-panelled passageways through entire complexes of houses whose proprietors have combined for such speculations. Both sides of these passageways, which are lighted from above, are lined with the most elegant shops, so that such an arcade is a city, even a world, in miniature.’ (Walter Benjamin, The Paris of the Second Empire In Baudelaire).

Restored in the late 90's, and with a collection of contemporary luxury boutiques (anyone fancy a pair of Christian Louboutin shoes?), Galerie Vero-Dodat gives a genuine flavor of the feel of the prototypical Parisian luxury arcade, and allows us to imagine how this new building type allowed the emergence of an activity that was to define a whole new social class. The arcades represented a new way of ordering the public realm, providing an alternative to both paris' labyrinth of small streets and the grandiose civic spaces carved out of them. The Parisian arcades were a decorous theatrical space, set up purely for the purposes of commerce and of display. They were destinations as well as thoroughfares; the way they cut through the blocks reorganized the City and provided the prototype for the later large scale urban moves implemented by Baron Haussmann. They reflected the rise to power of the bourgeoisie, a power based on commerce, manufacturing and purcasing power, rather than hereditary peerage. During their heyday there were over 100 arcades in Paris- only 21 remain today.

It's worth pausing to take stock of your impressions of the environment created by the Galerie. It's an ambiguous space, in many ways - neither inside, nor outside; both expansive and yet intimate, artificially lit by night, and ambiguously lit by day. The storefronts have the scale of a piece of furniture - marquetry rather than masonry. But despite the light washing down from above, the space feels a little claustrophobic - an uncomfortable scale for a public space in which we mingle with strangers. While the intimacy may have been appropriate for an emerging and somewhat timid class, once the bourgeoisie grew more self-confident and more established, they would eventually search for grander settings more reflective of their self-image.

The birthplace of this unique building type is located just a short walk away: it was in the nearby Palais Royal where the first arcade (now long gone) was originally created. Leaving Vero-Dodat and heading west, walking through the Place du Valois, fans of "Emily in Paris" will recognize the fictional headquarters of the "Savoir" advertising agency. Parisians may cringe at the way they are portrayed in the series, but they will agree that at least Emily had the good sense to take her first lunch break in the wonderful surroundings of the Palais Royal.

3. Palais Royal: an escape from Versailles

On the left: the "Galerie de Bois" was the first

shopping arcade ever built, and pre-dates the French revolution. On the right -

it was eventually replaced by the much grander Galerie d'Orleans - but all that

remains today are the granite columns.

On the left: the "Galerie de Bois" was the first

shopping arcade ever built, and pre-dates the French revolution. On the right -

it was eventually replaced by the much grander Galerie d'Orleans - but all that

remains today are the granite columns."For a gregarious people like the French, their pleasure is society" - Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle, Phillipe d'Orleans' architect, landscape architect and chief entertainment planner.

As we enter the serene environment of the Palais Royal, it is hard to imagine that in its heyday it was the Times Square of Paris, gambling, entertainment as well as a multitude of other opportunities to be led astray. The Palais Royal was Paris's very own Sin City.

Initially built as Cardinal Richelieu's palace about 150 years before the French Revolution, the Palais was expanded as part of a speculative real estate venture by its owner Phillipe Duke of Orleans, cousin of the ill-fated King Louis XVI. Phillipe was keenly aware that he lived in a society in need of entertainment: at his nearby property of Parc Monceau he had created Paris' first pleasure garden - an example of picturesque landscape designed as a conscious reaction to the symmetries of Versailles. In a similar vein he saw the goings-on at the Palais as an antidote to the strict formalities of the Versailles court and ended up creating what was quite possibly the western world's first permanent retail/entertainment destination.

The courtyards of the Palais Royal became the public salons of the city. In between the twin pairs of colonnades of the now empty middle court stood the Galerie de Bois, a 5-bay wooden structure built in 1786 that spawned the craze for building shopping arcades that occurred over the next half-century. In addition to the Galerie de Bois, other attractions at the Palais included a huge circus-like space half-buried in the ground, located where the gardens now stand, and two performing arts theaters. The perimeter stone building arcades were lined with boutiques, cafes and restaurants.

The Galerie de Bois was eventually replaced in 1936 by its successor, the elegant glass and steel roofed Galerie d'Orleans. However, Phillipe's successors did not have his political clout: in the 1830's prostitutes and gambling were were banned from the Palais Royal, and as a result it quickly began to lose its appeal. Described by French author Honore de Balzac as "cold, lofty... a sort of greenhouse without flowers", the Galerie D'Orleans became the first dead mall in the history of retail. People regretted the lost intimacy, the lost opportunities to indulge in vice, and longed for the old wooden galleries. The new Galerie was eventually torn down in 1935, but not before it had influenced many of the grand galleries in Europe (such as the Milan Galleria and the GUM department store), its influence extending beyond the seas to shopping malls such as the Dallas and Houston Gallerias.

Paradoxically it was the very rigidity and stratification of pre-revolutionary society, with its strict social hierarchies and equally strict dress codes, that allowed for the intense co-mingling that took place in the Palais. You could readily identify - and greet - your peers in public, and you knew who you could look down on and who you needed to look up to. The clothes made the man and determined behavior. As post-revolutionary social hierarchies frayed and public social identities became less obvious, sociologist Richard Sennett has suggested that this led to fundamental changes in how the public realm was perceived and inhabited. Philosopher Hannah Arendt further suggested that "the emergence of the social realm... is a relatively new phenomenon whose origin coincided with the emergence of the modern age". The social realm was a newcomer, neither part of the private realm nor the public political realm. It was a realm where you were surrounded by people whose social status was indeterminate - you were in effect socializing alongside strangers, in new settings specifically designed for that purpose. Attire, as we shall see, became a fundamental part of navigating through these new social spaces.

Today the Palais Royal is a favorite destination for Parisians looking for a little peace an quiet - a respite from the hubbub of the metropolis. As we leave it through its north western peristyle, we do have an opportunity to immerse ourselves in the long lost world of the Galerie de Bois by having a meal at the Grand Véfour, Paris' oldest restaurant. Founded in 1784, just in time for the French Revolution, the two-Michelin starred Véfour has had an illustrious list of diners over the centuries, including such luminaries as Victor Hugo, Jean-Paul Sartre and Jean Cocteau, all commemorated by brass plaques on the restaurant's chairs; it is also reputedly where Napoleon Bonaparte proposed to Josephine.

4. Galerie Vivienne: the haunt of the flâneur

The Galerie Vivienne, still a popular destination

today, is made up of a series of interconnecting spaces that house over

56 businesses, from specialty retailers and bookstores to food & beverage

establishments. The arcades became the haunt of the flaneur- the prototypical

people watcher and window shoppers

The Galerie Vivienne, still a popular destination

today, is made up of a series of interconnecting spaces that house over

56 businesses, from specialty retailers and bookstores to food & beverage

establishments. The arcades became the haunt of the flaneur- the prototypical

people watcher and window shoppers

"For the flâneur...the city is divided into its dialectical poles. It opens itself to him like a landscape, it encloses him like a room". Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project.

The Galerie Vivienne and its immediate neighbor the Galerie Colbert were opened in the 1820's to feed off the popularity of the adjacent Palais Royal - foot traffic is after all the lifeblood of retail. Though not the first arcades to be built following the success of the Galerie de Bois, they were some of the most aspirational, seeking to attract an upscale clientele. Galerie Colbert has been transformed into an exhibition space, so it is the adjacent Vivienne that is of interest today. Unlike the typical arcade that is a straight cut through a block, Vivienne had to be cut through a series of pre- existing buildings, and unfolds as a series of spaces of different scales. Vivienne thus becomes a series of indoor/outdoor rooms, both grand and intimate, housing a series of cafes, high end boutiques, beauty salons, art galleries, a flower shop, a bookstore, all unified by a beautiful mosaic floor. The arcade eventually takes you down a series of steps, turns left and leads you to the exit on the narrow Rue Vivienne.

As you stroll through the arcade indulging in a little window shopping (currently over 56 businesses call Vivienne home) you will be re-enacting the ritual of the flâneur. A man of leisure, first appearing in the literature of author Honore de Balzac and poet Charles Baudelaire, he was an urban tourist enjoying the spectacle of the City. According to Benjamin, “It is in this world that the flâneur is at home...To him the shiny, enameled signs of businesses are at least as good a wall ornament as an oil painting is to a bourgeois in his salon”. Unlike his fellow citizens who are perpetually harried by the chores of daily life, the flâneur roams where his fancy takes him, “right or left, without rhyme or reason”. Flânerie was seen as a sign of critical intelligence and moral stature, an exercise in freedom that would ennoble the spirit. The loitering and idleness of the flâneur were a deliberate counterpoint to the ethos of productivity: he was a both a product of and a reaction to the rapid changes brought about by industrialization. He represented the resistance of the daydreamer to the rise of industry and commerce- yet the products of industry and commerce were the focus of his daydreams.

The flâneur turns his nose up at vulgar parades of entertainment and consumerism: he keeps a critical detachment, and he is a keen observer of human mores and physiognomies, the ultimate people watcher. Poet Charles Baudelaire contrasted the flaneur with his counterpart the badaud (a city bumpkin) who gapes at shop windows, is easily awed by the proliferation of goods, and lacks in intelligence and critical spirit, dragged along passively by the crowd.

Sociologist Georg Simmel, in his famous 1903 essay "the metropolis and mental life", speculates on the psychological causes of the flaneur's blasé attitude : "Instead of reacting emotionally, the metropolitan type reacts primarily in a rational manner... the essentially intellectualistic character of the mental life of the metropolis becomes intelligible as over against that of the small town which rests more on feelings and emotional relationships." According to Simmel, emotional detachment is a reaction to the proliferation of external stimuli provided by the modern metropolis and its lack of social intimacy - what we might refer to today a lack of a sense of community. It was a way of dealing with an increasingly complex public realm, one where the individual finds themselves surrounded by strangers. This attitude survives to this day, and underlies contemporary retailers' obsessions with the elusive "sense of community", and their focus on wanting to capture both "the head and the heart" of today's shoppers- going against the grain of the "essentially intellectualistic character of the mental life of the metropolis" in order to create an emotional connection with their customers. It's all about seducing the flâneur...

The deliberate nonchalance and idleness of the flaneur, a bit of a show-off and a bit of a dandy, reached a climax in the 1840's, when it became fashionable for flâneurs to take turtles for a walk in the arcades. Unfortunately we do not have time for such dallying, since we need to make our way up Rue Vivienne and past the old Stock Exchange to our next destination, the Passage des Panoramas.

5. The Passage des Panoramas: the seductions of consumption

On the left: The Passage des Panoramas was a popular

destination in its heyday, but eventually fell out of favor like many of the

other Parisian Arcades. It was one of the settings for author Emile Zola's

novel "Nana", where he explored the many dangers of temptation. On

the right – today it has regained some of its former popularity, and features a

mix of boutiques, cafes and restaurants.

On the left: The Passage des Panoramas was a popular

destination in its heyday, but eventually fell out of favor like many of the

other Parisian Arcades. It was one of the settings for author Emile Zola's

novel "Nana", where he explored the many dangers of temptation. On

the right – today it has regained some of its former popularity, and features a

mix of boutiques, cafes and restaurants.

Today the southern entrance of the Passage des Panoramas is particularly uninspiring - the drab mid-century building that replaced the one that had stood there for over a century reduced the double height portal to a single story - but walk a few dozen meters and you'll soon reach the original arcade, one of the very first to be built. You'll likely find yourself in the midst of bustling activity, with a series of food establishments and shops selling vintage postcards, coins, autographs and old stamps. Remnants of the original tenants still remain, such the Stern printing works signage overhead (The name has been appropriated by the current tenant, The Stern café, whose front door is guarded by a winged coyote). The Théâtre des Variétés, dating from the early 1800's, and the setting for Emile Zola's novel Nana, remains a popular venue for shows and comedies; however the two giant panoramas that gave their names to the passage and that flanked the entrance on the Boulevard Montmartre are no more.

These were a pair of rotundas with a central viewing platform surrounded by a 360 degree painted image, creating something akin to today's "immersive" experiences. The first rotunda featured a view of Paris taken from above the Palais des Tuileries, the second a painting depicting the attack on Toulon by the English in 1793. Panoramas became hugely popular in the 19th Century, and attracted large crowds throughout European cities until the rise of the moving picture rendered them obsolete.

Gaining a panoramic view of the world was a characteristic of the enlightenment period as it transitioned to the modern age, whether it was the famous "encyclopedie" of Diderot and d'Alembert, collections of plant species in the new palm houses, collections of artifacts in museums, or the gathering of the world's manufactured objects at the Crystal Palace in 1852 - an encyclopedic panorama of the products of the industrial revolution. Older and more traditional forms of cultural transmission such as narration were being replaced by relatively superficial display of goods and information, and in its turn information was being increasingly replaced by pure sensation. In the Panorama, instead of carefully crafted objects, the vitrines were filled with the goods of industrial production. Proliferation led to superficiality: Detached from their manufacturing context, they have lost their storyline and threaten to turn the previously engaged customer into a passive spectator and consumer of goods and experiences. According to cultural critic Walter Benjamin, a story « bears the marks of the storyteller much as the earthen vessel bears the marks of the potter’s hand. » Benjamin thus identified the arcades as representing a turning point in society. The factory had displaced the workshop, and the noble craftsman had been replaced by the anonymous factory worker. Novelty, rather than craftsmanship and tradition, had become the consumer's focus.

In his novel Nana, published in 1880, author Emile Zola describes the intoxicating aspect of this panorama of cheap goods. Nana, part-time actress and full-time courtesan, adored the Passage des Panoramas. The false jewelry, the gilded zinc, the cardboard made to look like leather, had been the passion of her early youth...when she passed the shop-windows she could not tear herself away from them. By placing his courtesan in this setting, Zola seems to suggest that in the passage everything and everyone is cheap, shallow and for sale. The passage itself is as seductive and as perfumed as Nana - Zola describes the the strong savor of Russia leather, the perfume of vanilla emanating from a chocolate dealer's basement, the savor of musk blown in whiffs from the open doors of the perfumers - all enveloping the consumer in a seductive world of sights and scents, a world described by Benjamin as a "Phantasmagorical" escape from reality. It was a place where buying was no longer done out of necessity, but had become a form of escapist entertainment, a search for instant gratification. It was a world whose siren song threatened to turn the discriminating flaneur into the passive, dull-witted badaud - a consumer all but consumed by the objects of his desire.

Before you leave the Panoramas it may be worth indulging in a meal at "Canard & Champagne" (Duck and Champagne - the name says it all). Although the food is allegedly delicious, hopefully you will have more self-restraint than many of Zola's characters, and it won't be the start of a journey down the slippery slope of obsession, financial ruin and oblivion!

6. The Grand Boulevards: society on display

In both art and life the stability of the Ancient Regime had

been replaced by a focus on surface appearances and the ephemeral. The

Impressionists celebrated movement, impermanence and the great outdoors.

In their heyday it was the life of the boulevards, and not the arcades, that

impressed them. On the left, Camille Pissarro’s painting of the Boulevard

Montmartre; on the right, a café scene by Louis Sabatier.

In both art and life the stability of the Ancient Regime had

been replaced by a focus on surface appearances and the ephemeral. The

Impressionists celebrated movement, impermanence and the great outdoors.

In their heyday it was the life of the boulevards, and not the arcades, that

impressed them. On the left, Camille Pissarro’s painting of the Boulevard

Montmartre; on the right, a café scene by Louis Sabatier.

The Passage des Panoramas will discharge you onto the Boulevard Montmartre, one of Paris' Grands Boulevards. These wide thoroughfares form a ring around Paris' Right Bank neighborhoods, and were created when the city's outer fortifications were torn down during Louis XIV's reign (boulevard and bulwark derive from the same etymological root). These were mostly surrounded by orchards at the time of their demolition, but as the city grew, the lots lining them filled out, and they became a popular destination in the city.

They became of course the prototype for the more ceremonial urban interventions created by Baron Haussmann: his boss Napoleon III had spent a few years in exile in London and had been impressed by London's Georgian-era expansion with its wide, ordered thoroughfares. The layout of Washington D.C. may have been an model too - its plan by French engineer Pierre Charles L'Enfant dates from 1791. If the Palais Royal had been the anti- Versailles, Haussmann was now introducing the allées of Versailles back into Paris (as L'Enfant did in D.C), imposing a Napoleonic order and discipline onto the chaotic layout of the city's working class neighborhoods. The buildings lining the original Grands Boulevards however pre-date the strict architectural guidelines imposed by Haussmann, and as a result these have an energy and liveliness missing from most of the Haussmann-era boulevards. Nevertheless , the openness of the Parisian Boulevard liberated the flow of people and goods from the constraints of Paris' medieval alleyways, allowing much greater freedom of movement within the city.

If the flaneur was born in the shopping arcade, the boulevard is where he came of age. Writer Honoré de Balzac was a flaneur par excellence - he was the great chronicler of the boulevard, hunting for clues in order to "read" passers by - determining their station in life by observing the way they walked, the way they dressed. For Balzac, the boulevard was where the spectacle of modernity was on show, where "the great poem of display chants its stanzas of color from the Madeleine to the gate of Saint-Denis".

With the appearance of mass production came the emergence of the masses (Hannah Arendt characterized the 19th Century as one of transition between an aristocratic society to a class society to a mass society). From the time of the French Revolution through to the 1830‘s, the population of Paris had nearly doubled. The Parisian crowd fascinated poets and artists alike: the impressionists were the first to attempt to capture the murmuration-like ebb and flow of the passers by, with Camille Pissaro painting countless versions of the Boulevard Montmartre across the seasons and the time of day. Poet Charles Baudelaire described the flaneur's joy of immersing himself "in the multitude, in the rising swell, in movement, in the ephemeral and infinite". Previously art and literature had celebrated stability and social hierarchy; now it was celebrating movement and impermanence, a celebration that was to culminate in the invention of the moving picture. Almost a century later author Virginia Woolfe was to echo the same sentiments when talking about London's premier shopping street: "The mere thought of age, of solidity, of lasting for ever is abhorrent to Oxford Street". Motion, rapid progress were becoming symbols of the modernity (the railroads gave for the very first time the ability to speed through the landscape); the boulevards were ushering in the dawn of the modern age.

But even flaneurs can become weary of their wanderings, and will need a respite from the restless throng of the crowd. Thankfully, the great Parisian institution of the terrasse de café is close at hand - "s'installer en terrace" means to make oneself at home on the cafe terrace, to sit back and watch the great spectacle of the Parisian boulevard, which had become the mirror of bourgeois society. The boulevard was a theatrical setting through which citizens could observe the behavior of their peers - an experience echoed within the many theaters, cafes, and other places of entertainment that sprang up along them (the Theatre Des Varietes is still located next to the Passage des Panoramas today). These were all spaces for the display of affluence, of conspicuous consumption, and of fashion. The passages couverts had enabled the bourgeoisie to emerge out of their homes; now the boulevards were allowing the bourgeoisie to emerge out of the arcades and to put themselves on display en plein air. The intimacy of the passages now seemed anachronistic, their scale provincial in comparison to the lively and grandiose panorama of Parisian society provided by the boulevards.

7. Passage Jouffroy and Passage Verdeau: a swan song of glass and steel

On the left: Passage Jouffroy. On the right: Passage Verdeau. Both were

built towards the end of the arcades era, and both feature extensive use of

structural cast iron (author's photographs)

On the left: Passage Jouffroy. On the right: Passage Verdeau. Both were

built towards the end of the arcades era, and both feature extensive use of

structural cast iron (author's photographs)

The twin passages of Jouffroy and Verdeau, opened in 1847, were among the last arcades to be built, in an attempt to feed off the popularity of the Passage des Panoramas. By then however the novelty of the passage was beginning to wear off; gas lighting, once unique to the passages, had spread to the City's boulevards. Just a few short years after Jouffroy and Verdeau opened, entrepreneur Aristide Boucicault would cement the decline of the Passages when he began the radical transformation and expansion of his shop Le Bon Marche into the world's first fully fledged department store.

Jouffroy and Verdeau are notable for their embrace of cast iron. The use of steel and glass had previously been confined to creating the glazed roofs of the passages; here cast iron takes over and forms the structure of both walls as well. The extensive use of iron began to challenge the prevailing aesthetics of neoclassicism, inviting the engineer into the architect's realm. Iron was extensively used for arcades, exhibition halls, railway stations – buildings which served transitory purposes, and which were emblematic of the emerging modern age. This was the beginning of a paradigm shift in architecture, in which buildings were to become an expression of structure, nowehere more so than in Paxton's Crystal Palace (1851), in Baltard's steel pavilions for the new Les Halles market (1870), and of course in Eiffel's eponymous tower completed in 1889.

The novelty of cast iron construction in the arcades (like the inevitable fate of all novelties) eventually wore off, and the sometimes incongruous juxtaposition of businesses found there were no match for the seductive ordering and curation to be found in the new the department stores. In many ways the arrival of the department store did to the arcades what the suburban shopping malls did to America's donwtowns - they provided a more cohesive environment, where bigger was better. By the 1860's the arcades were beginning to be torn down, or were becoming decidedly downmarket as competition from the department stores began to drive tenants out of business.

The loss of status of the arcades, and their abandonment by the moneyed classes, gave them a second, much less lucrative, lease on life as the haunt of the lower middle and working classes. Arguably what they lost in cachet they gained in authenticity, becoming somewhat chaotic, and occasionally a little louche, some housing hotels where rooms could be rented by the hour, away from the prying eyes of the boulevards.

The arcades however remained a source of literary fascination for early 20th century authors such as Walter Benjamin and Surrealist Louis Aragon. Walter Benjamin was convinced that the Parisian Arcades held the key to the roots of the modern age, and spent years assembling literary fragments, quotes and aphorisms into his monumental work entitled simply "The Arcades Project", left unfinished at his death trying to escape from Nazi-occupied France. In Benjamin's mind the arcades represented the real, unofficial record of the momentous changes taking place during the first half of the 19th Century, as opposed to the "official" history one might find in history books . For Aragon, the commercial value of the arcades had been superseded by their poetic value: in his novel "The Paris Peasant", he describes the enduring power of the arcades: "Although the life that originally quickened them has drained away, they deserve, nevertheless, to be regarded as the secret repositories of several modern myths: it is only today that they have at last become the true sanctuaries of a cult of the ephemeral." The Surrealists saw the arcades as a window into the innermost workings of the mind and the imagination - a quasi Freudian manifestation of repressed human desires, reflected in incongruous window dispays, surprising juxtapositions of objects, and obscure books filling the shelves of bookstores. Rather than seeing the objects and commodities filling the arcades as status symbols (a very bourgeois attitude), the surrealists appreciated them instead for their artistic and poetic value, just as Benjamin had appreciated them for their historical value.

In order to understand why the arcades lost their commercial allure and became passé, we need to step out of Verdeau onto the Rue du Fauborg Montmartre, make a left turn past the extraordinary storefront of the "A la Mère de Famille" confiserie shop, and head towards the largest department store in Europe, the Galeries Lafayette.

8. The Galeries Lafayette: retail reinvented

On the left: The grand

staircase of Le Bon Marche bears a striking resemblance to the grand staircase

of Garnier’s Paris Opera House; on the right: the Galeries Lafayette to this

day retains the grandeur of 19th Century Department stores.

On the left: The grand

staircase of Le Bon Marche bears a striking resemblance to the grand staircase

of Garnier’s Paris Opera House; on the right: the Galeries Lafayette to this

day retains the grandeur of 19th Century Department stores.

The central rotunda of the Galeries Lafayette is an impressive space. Looking up at its 4 stories, capped by an impressive dome of glass and steel, you are at the very heart of the shopper's universe -an Aladdin's cave of consumer goods that hold out the promise of a better life. If the arcades were a street in miniature, then the department store became a whole city in miniature, through which one could wander in wonder. (Walter Benjamin had suggested that the department store was the last hangout of the flâneur, where "he roamed through the labyrinth of merchandise as he had once roamed through the labyrinth of the city"). Shopping for pleasure had finally eclipsed shopping for necessity: prior to the advent of the department department store, middle-class women would typically send their servants out to perform what was seen as an unfulfilling chore. The common practice of haggling over prices (which were typically not displayed) was not something to look forward to. Buying was practical and functional, and impulse buying non-existent.

This changed with the arrival of the Bon Marché, which was transformed by its owner Aristide Boucicault from a medium-size dry goods store into the world's first department store in 1852. This was the year following London's Great Exhibition, when the vast Crystal Palace had been erected in London's Hyde Park and filled with a cornucopia of goods from around the world - goods which all happened to be for sale (Queen Victoria herself made a number of purchases there). Boucicault set out to create his own version of this overwhelming display of goods, buying adjacent blocks to enlarge his store, and introducing a number of innovations that included fixed prices, ever-changing window displays, recurring sales when bargains could be found, bulk purchase-driven competitive pricing, and heavy advertising in local papers.

This was a victory of quantity over quality, fed by crowds arriving on omnibuses via the new boulevards as well as by visitors arriving from the provinces via the new railway system. The tremendous success of the Bon Marche was followed by a slew of would-be competitors, including the Grands Magasins du Louvre (1857), Printemps (1865), La Samaritaine (1870), and finally the Galeries Lafayette in 1893. Bigger was better, and the Galeries Lafayette eventually grew to its current size of 650,000 sf, second only to Macy's in Herald Square. If the flâneur had traditionally been male, he had now become female: the department store was a ladies' paradise, to borrow from the title of Emile Zola's novel, set in a fictitious department store based on Le Bon Marché. All of the amenities of department stores, incuding a salon de the and restrooms for women, contributed to the idea that spending the day in the store, pampered in luxurious surroundings, was better than spending the day at home.

If the glazed vitrines of the passages created a boundary between shoppers and commodities, Zola describes how its removal in the department store unleashed unrestrained desire in the department store's clientele: It was Woman the shops were competing for so fiercely, it was Woman they were continually snaring with their bargains, after dazzling her with their displays. They had awoken new desire in her weak flesh, they were an immense temptation to which she inevitably yielded, succumbing in the first place to purchases for the house, then seduced by coquetry and, finally consumed by desire. (Before we accuse Zola of overt sexism, we should remind ourselves that his novel Nana was about desire being awoken in men's weak flesh, Nana being herself an immense temptation to which they inevitably yielded, consumed by desire and ruining themselves in the process).

The department stores did provide an alternative social setting to the domestic salon, and opened up the public realm to unchaperoned women who had previously been house-bound: it was only with the advent of the department store that "respectable" middle class women could legitimately venture out alone in public. The Bon Marche and its imitators Printemps and the Galeries Lafayette had become places to see and be seen, part of the social world of the bourgeoisie (there is a striking similarity between the design of these palaces of luxury and that of the adjacent Paris Opera House, with its opulent ceremonial staircase). Shopping had become aspirational, a symbol of one's social status within the growing bourgeoisie - a world away from the markets and workshops of the Halles neighborhood. Boucicault was to shopping what Henry Ford was to the automobile: he gave his clientele the store they never knew they wanted.

After you wander through the shopper's paradise of the Galeries Lafayette , it's worth making your way up to the roof. Once outside, you'll enjoy an 180-degree panorama of the city, and an opportunity to dine at the Galeries' yearly summer pop up restaurant (this year it's the humorously named Créatures, offering vegetarian cuisine). Gazing over the city, you may echo the feelings of Baudelaire's flâneur, as he "watches the flow of life move by, majestic and dazzling. He admires the eternal beauty and the astonishing harmony of life in the capital cities, a harmony so providentially maintained in the tumult of human liberty. He gazes at the landscape of the great city, landscapes of stone, now swathed in the mist, now struck in full face by the sun. " Standing on the roof of the Galeries Lafayette, looking out over the rooftops of the city of Balzac, Baudelaire, Zola, Pissarro, the Surrealists, and Walter Benjamin, perhaps you will be as inspired as these writers and artists were by the seductive beauty of the capital of the 19th century.

Conclusion: the legacy of the arcades - settings for the creation of self and society

A scene from the Galerie de Bois in the Palais Royal in the

early 1800's: do we shop to express our individuality, or do we shop in order

to reinforce our sense of belonging to a particular social class?

A scene from the Galerie de Bois in the Palais Royal in the

early 1800's: do we shop to express our individuality, or do we shop in order

to reinforce our sense of belonging to a particular social class?

Today, shopping continues to have the ambivalent status that Zola assigned to it in "The Ladies' Paradise": it is often regarded as a frivolous, unproductive and self-indulgent activity. Author Susie Hennessy's summary is typical in that respect: "shopping has become an end unto itself, with no purpose other than as a distraction...We consume merchandise just as we digest information, ever eager to obtain more things and follow fashion. It has become a panacea for feeling down, an activity to pass the time, entertainment via escapism... The availability of refreshments, restrooms, movie theatres, and even comfy armchairs in shopping malls reinforces the illusion of being at home, all the while surrounded by fantasies of other more exciting, more perfect lives; shoppers acquire new identities via the stores they frequent. Women undergo cosmetic counter "make overs" in department stores in order to become someone else".

But the passive consumption described by Hennessy misses a fundamental raison d'être of shopping: we are social beings after all, and rather than shopping to distract ourselves, perhaps we shop in order to build our public, social personas. We shop not just to indulge the person we are, but to conform to the dress and manners of our perceived peer group: we shop to create the person we want to appear to be. That is the paradox of shopping - we shop both to stand out and to conform. Balzac, in his 1830 Treatise on elegant living: on the importance of appearance, had suggested that the question of attire “is one of enormous importance for those who wish to appear to have what they do not have, because that is often the best way of getting it later on." Subtle differences in dress and accessorizing were becoming key to creating one's identity: "The manner in which his cravate is bowed and knotted "separates a man of genius from a mediocre one". For poet Charles Baudelaire, fashion, cosmetics and other adornments were an intrinsic part of presenting oneself in public: people needed to hide their natural selves so as to become the person they wished to appear to others: "Fashion must be thought of as a sublime distortion of one's nature, or rather as a permanent and constantly renewed effort to reform nature." Ever the dandy, Baudelaire had scant respect for the unadorned.

The arcades were the settings where one could create and display these newly minted public personas, and give one the the sense of belonging to the newly minted bourgeoisie. Vero Dodat, Vivienne, the Passage des Panoramas, together with the boulevards and the department stores, were all settings in which the social rituals of the emerging middle classes could be acted out: these settings were an important part of creating class identity - in effect a new social realm, distinct from the private world of the house and the public world of business and politics.

Suburban shopping malls today perform much the same function as did the Parisian shopping arcades, providing an environment that gives the suburban middle classes a sense of their identity - a place to perform a little people-watching, a place for teens to play at being out in public, a place to cultivate and forge one's public image, a place to adopt the identifiers of one's class and of one's perceived or desired status, whether by buying the latest in athleisure wear or purchasing a sharp new suit (the French word for business suit is costume ). The mall, Main Street and the High street and other shopping venues are where we go to create how we want to be seen, based on the brands we purchase - brands that reinforce our desired self-image and allow us to define how we will be perceived in the different social situations we participate in.

A much-repeated claim within the retail industry is how retail "creates community". Based on its Parisian birth and evolution I would counter that shopping is primarily a social experience and as such it builds social bonds rather than communal bonds. It does so in two primary ways:

- focusing on the self, it allows us to purchase the goods (clothes, accessories, cars, furniture, real estate) that go into the social "presentation of our selves in everyday life" (to borrow a term from sociologist Erving Goffman), helping us define our public persona (whether for formal or casual social encounters), and reinforcing a sense of belonging to a particular social demographic.

- focusing outside the self, it gives us physical places where we can enjoy the ever-changing spectacle of society, a welcome relief from the spectacle streaming on our devices. Retail creates activation of the public realm, fostering informal social interactions and encounters with those beyond our immediate communities, friends, family, co-workers and neighbors - it puts us in the company of strangers. These commercial public spaces will also give identity to a particular neighborhood - for example many of San Francisco's neighborhoods are anchored around a retail street, and both Main Streets in the States and High Streets in England give identity to the towns surrounding them. Even the suburban mall creates the seeds of a place-based identity.

The arcades were the first spaces specifically dedicated to middle class social presentation and social interaction; they were in due course rendered obsolete when these activities moved to the grander settings of the boulevards and the department stores, eventually finding their way to the mid-century shopping mall, which in its turn helped forge the identity of a new class of suburbanites. Arguably these spaces of physical presentation and interaction, in effect spaces of "loose" belonging, are needed now more than ever in our current situation of digital retrenchment into our isolated private worlds. By allowing us to create our public persona and situate ourselves within the ever-increasing complexity of today's society, shopping plays its part in reinforcing the fragile social bonds that hold our fragmented society together.