The city is like a great house, and the house in its turn a small city.

Leon Battista Alberti, On the Art of building in Ten Books (mid- 15th Century)

We've learnt how event segmentation theory and the doorway effect suggest that a series of interconnected indoor or outdoor rooms of different scales might become a better receptacle for future memories - these experiments point to ways we can mentally inhabit spaces. Our homes do this for our childhood as they organize space, thoughts, memories and activities. Despite the oft repeated child's illustration of what a house should look like (central door, 2 windows, pitched roof and smoking chimney), our homes are primarily experienced as a sequence of interior spaces. To a certain extent the city and suburbs consist of interior spaces too: office spaces, libraries, shops, churches, subway stations. But step outside into the public realm and we leave spatial enclosure to find ourselves in a world of vast empty spaces filled with object buildings - an unsheltering world in which we are outsiders. Gone are the "large number of places which must be well-lighted, clearly set out in order, at moderate intervals apart“. Instead it's a world of standalone buildings each clamoring for our attention - individual fragments that do not necessarily cohere.

Can we be made to feel at home in the public realm?

The post-industrial public realm has certainly had its challenges: it is often no more than the leftover space between roads and the private realm. The 20th century exodus from cities and the corresponding growth of suburbia has further contributed to its disintegration. Can the the public realm acquire the same emotional and mnemonic resonance as the rooms of a house? Can it be designed in such a way that it echoes how our minds perceive and remember events?

If the suburbs represented the fraying of the public realm, suburban retail did try to come to the rescue: the new shopping centers that followed suburban expansion at the beginning of the 20th Century offered opportunities to rethink public space. Notable examples include Market Square at Lake Forest Illinois (1916), Kansas City's Country Club Plaza (1923), and Dallas' Highland Park Village (1931). Although these were all vehicular destinations, they provided a variety of pedestrian public spaces; more importantly they punctuated the sameness of the suburban landscape by providing outdoor rooms of different scales reminiscent of the town squares of Europe. The notion of providing public rooms for suburbanites took an interesting detour in the 1950's, a detour that completely changed the nature of suburban public space. This detour was called the enclosed shopping mall.

Suburban Memory Palaces

Public rooms: A cross between New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art (left) and Gruen's Southgate Center (center), Dallas' NorthPark Center (right) is both a thriving commercial center as well as a house of memories for those growing up in the surrounding suburbs. According to retail guru Paco Underhill, it was the Dalai Lama who described shopping as "the museum of the 20th Century".

Malls may be dying, but mall nostalgia is alive and well: the internet is full of reminiscences about long-gone malls and how they provided memorable settings for those who grew up around them, complementing the suburban backyards that had replaced streets and squares as an informal outdoor gathering space. In "Meet Me by the Fountain", author Alexandra Lange describes shopping mall maestro Victor Gruen’s belief that residents of the 1950's versions of suburbia had unfulfilled psychological needs due to the uniformity of the suburban environment and its lack of public social spaces. Gruen thought that the solution was to recreate the liveliness and variety of European cities, typically organized around pedestrian movement through streets and plazas - a sequence of walkable outdoor public rooms. He was in effect proposing a facsimile of the city, based on the archetypes of street and square, but his innovation was to reimagine these outdoor rooms as a series of large-scale indoor spaces - a contemporary version of the grand European Gallerias of the 19th Century. And so the indoor shopping mall was born, a new building type that proliferated throughout the United States from the 1950's to the 2010's. At Southdale Center in Edina, Minnesota, Gruen created the first two-level enclosed mall in the US, featuring shops and department stores pinwheeling around a central triple-height Garden Court atrium, top-lit by clerestories, animated by escalators and a kinetic fountain. Gruen was trying to bridge the gap between the private spaces of the suburban house and the uninspiring environments of America's gridded downtowns that suburbanites had left behind- a spatial « missing middle» of sorts.

While many subsequent malls were formulaic one-story versions of Southdale (the so-called "dumbbell" plan, a continuous row of shopfronts with a department store at each end, repetitive and thus eminently forgettable), there were some notable exceptions. One of the more enduring mall success stories, Dallas' NorthPark Center, opened in 1965 and is still going strong. The mall's original architect was EG Hamilton of the architectural firm Omniplan, and Lange describes how, while working on schemes for the center, Hamilton happened to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where he experienced a revelation - it occurred to him that the sequence of spaces at the museum was a lot more interesting (and memorable) than the sequence of spaces to be found in the typical dumbbell mall . The result at NorthPark was a spatially modulated environment, where one wanders through a variety of interconnected rooms punctuated by striking pieces of art. This sounds rather similar to Cicero's "large number of places which must be well-lighted, clearly set out in order, at moderate intervals apart", full of striking images: the spaces of the mall see-saw between the intimate and the awe-inspiring, as do the objects of the shoppers' attention, which could be anything from a from a pair of socks at Banana Republic to Mark di Suvero's monumentally impressive, 48-foot-tall, 12-ton Ad Astra sculpture. Hamilton had created something closer to Gruen's original vision, better able to frame memories than the uninspiring common areas found in many malls and had (perhaps inadvertently) uncovered an affinity between mall and museum. Museums had eventually succeeded cathedrals as the repositories of culture, and retail guru Paco Underhill relates how the Dalai Lama once described shopping as « the museum of the 20th Century ». NorthPark and other similar malls had become the new houses of the muses and memory for their surrounding suburbs. This may help explain the enduring appeal of the mall as a building type: it's as much a repository of memories as it is a place to peruse commercial goods.

The physical isolation of malls, separated as they were from a residential or mixed-use context, as well as their singular focus on retail, was very much a double-edged sword. On the one hand it allowed for a greater level of spatial experimentation than would have been possible in a more complex environment; on the other hand, that very separation created a one-dimensionality that left them vulnerable to the whims of consumers and the winds of time. Gruen eventually shifted his focus to urban environments, thinking that many of America's beleaguered downtowns could also benefit from the attention to walkability and the shaping of space that he had explored in his mall designs. Unfortunately, his pedestrian precincts (for example the one proposed for downtown Fort Worth) came too late, since by then most folks had relocated to the suburbs!

Gruen was however posing an important question: can public outdoor spaces exert the same hold on our memories as the interior worlds of the home and the enclosed shopping mall? Buildings are easily subdivided into sequences of rooms that can frame numerous memories, but the public realm with its ubiquitous grids less so. It generally manifests itself as an unsettling, uninviting and amorphous spatial continuum that provides few resting places for our thoughts. We are, however, at an interesting turning point in the history of the shopping mall, with many being rethought as outdoor mixed-use neighborhoods. This transformation entails an essential change in their nature - what was once a weekly or monthly destination needs to be turned into an everyday neighborhood. Going back to the distinction between different kinds of memorable spaces made at the beginning of part 1 of this essay (the sublime, awe-inspiring kind of memorable place versus the understated but familiar memorable place), the design challenge involved in transforming the suburban public realm is finding ways to turn the imposing and impressive shopping mall into a sequence of places more akin to Joyce's Dublin - it's about moving away from designing a world made up of monumental objects, and focusing on the places in between the objects.

Intimacy in the Public

Realm

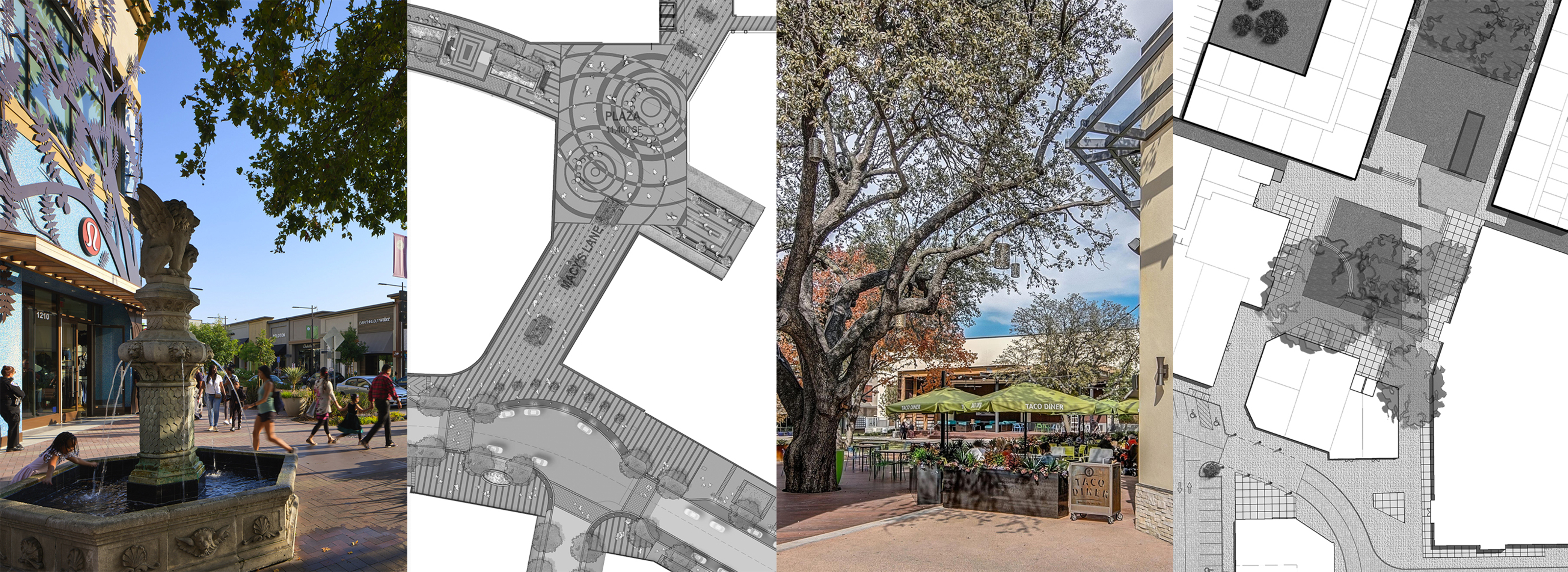

Outdoor rooms: On the left, Valencia Town Center in Valencia CA; on the right, Costa Plaza in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Places to hang out and savor the moment.

"Whoever knows how to lay out a park" wrote Abbé Laugier, one of the most popular and influential of mid-eighteenth-century architectural theorists, "will have no trouble in drawing up the plan according to which a town is to be built with regard to its extent and the site.… It will need regularity and fantasy, associations and oppositions, random incidents to introduce variety, great regularity in the detail, and confusion, clash and ferment in the whole". It's difficult to imagine a contemporary urban planner or engineer advocating "confusion, clash and ferment in the whole" - they would likely soon be out of a job. And yet as the suburbs continue to grow and struggling malls make way for outdoor mixed-use environments focused on the pedestrian experience, there are opportunities to create rich sequences of differentiated spaces, where the harsh logic of vehicular circulation no longer drives the design. These are environments that pay attention to how people move through space, to how they interact both physically and mentally with their surroundings - environments that foster memorable walks, and that take advantage of the deep affinities that exist between place and memory - environments that have those very qualities described by Laugier, as he evokes the intimacy of public parks and gardens.

Of course older traditional cities built over time exhibit that kind of spatial richness, with different environments and scales creating distinct settings appropriate for a whole range of uses, including shops, restaurants and cafés on the streets, and other uses such as workshops or studios in secondary streets and courtyards, with private gardens hidden mid-block. These more varied and modulated sequences of outdoor spaces are generally lacking in American post-industrial cities, constrained as they are by the straitjacket of the vehicular grid.

Outdoor rooms do still abound in many modern cities: William Whyte's "the Social Life of Small Public Spaces" contains many examples from New York; small pocket parks in particular form an appealing respite from the surrounding density. Kevin Lynch in "The Image of the City" suggests how the various urban spaces of Boston form an interconnected web in the minds of its residents, with retail landmarks acting as important markers and points of orientation. Gordon Cullen did the same for British towns in his "Townscape", developing the notion of serial vision, which has many parallels to the imaginary walks through memory places featured in the art of memory. On my desk sits a well-thumbed copy of Christopher Alexander's "A Pattern Language": it's full of clearly articulated and differentiated settings that can create moments of respite within an otherwise undifferentiated environment. The book enumerates a multitude of spaces at different scales that can form backdrops to various experiences and memories: shopping streets, gateways, small public squares, street cafes, food stands, courtyards, roof gardens, arcades, stair seats, private terraces, alcoves, built-in seats, framed views- the list is extensive. These can be choreographed to form striking and memorable spatial sequences, with a seductive rhythm of openness and contraction. I’ve experienced this in places like Bruges, Annecy, Verona, London, Paris, Barcelona among many others- a walk in one of these places may take you through a narrow street, under a portal, into a town square, through a loggia, over a bridge crossing a canal, into a tree-lined avenue. As suggested by Whyte, contemporary cities have their moments too - typically these are small secondary leftover spaces, often the stepchildren of grander urban moves.

So when we think of memorable urban spaces our mind might gravitate to grand gestures such as The Place des Vosges in Paris, Bernini’s St Peter’s Square in the Vatican, the Georgian Squares of London, or even Las Vegas Boulevard. However, there is also value in focusing on the creation of intimacy: places that are best thought of as allowing experiences to be remembered, rather than something to be experienced in and of themselves. The previously quoted passages by James Joyce and Colin Ellard provide vivid examples of the qualities of understated and everyday urban and rural places, and their relationship to memory and experience. It's the encoding specificity theory working hand in hand with event segmentation: the familiar surroundings trigger a chain of metaphors and associations, revealing the presence of the extraordinary in the everyday, a sudden juxtaposition of the sublime and the intimate, hinting at the interconnectedness of all things. In terms of pop psychology, we are at the apex of Maslow’s pyramid of human needs - past food and shelter, safety, past social needs and self-esteem - into the elusive realm of « self-actualization » and the transformative power of memory and the imagination, enabled and catalyzed by an emotional relationship to place.

I think we've forgotten about this hidden power of place because so many of the places that we experience on a day-to-day basis outside of our homes tend to be extremely homogeneous - whether it's our office cubicles, the strip malls where we shop, the inside of our cars where we spend way too much time, the grids of our cities or the endless roads of our suburbs - or the virtual spaces of our computers as we participate in one zoom call after the next.

What kind of design strategies can we adopt to give the places of the public realm the intimate mnemonic richness of our homes?

Design Strategies

for the Remembering Self

Intimacy and monumentality in the public realm: on the left, the olive trees at First Street Napa have a bonsai-like quality; on the right, an illuminated water tower at Forum Cuernavaca provides a contrast in scale to the surrounding pedestrian passageways.

Ultimately, it's the back-and-forth between the intimate and the sublime that will create compelling environments where our thoughts both trivial and lofty can find an echo. There is perhaps a not so surprising tendency within the design community to focus on the sublime. Here are some strategies that focus instead on the creation of intimacy, strategies that might help foster enduring memories:- Above all a pedestrian place: the environments that people seem to be drawn to most are those featuring exterior pedestrian alleys and plazas, where the scale is not dictated by vehicular circulation requirements, allowing for a highly modulated the spatial sequence.

- Articulating the sequence of places as a series of loosely defined outdoor rooms, each with distinct boundaries caused by a change of scale, change of direction or other way of creating thresholds.

- Some of these places may be seen as "positive" space - well defined and ordered - others might feel more like left-over spaces, wedged in between two buildings. The positive spaces tend to evoke awe; the left-over spaces tend to be more intimate and casual.

- Introducing landscaping elements (trees, planters) and topography to further help define outdoor rooms or to create thresholds between them.

- Creating changes in level as another kind of threshold between outdoor places.

- Creating rooms within rooms - for example using overhead trellises, retractable awnings, parklets or streateries, which create more intimate rooms within a larger outdoor room. Outdoor dining terraces in particular can benefit from these approaches.

- Juxtaposing sublime moments with moments of intimacy by varying the scale and appearance of buildings, some more monumental and springing from the ground, others allowing for the presence of a more articulated and granular ground floor that contrasts with the rigor of the building above.

- Encouraging retail tenants to pay attention to ground floor storefronts so that these can entice and engage the imagination (with a shout-out to the lost art of window dressing). Traditional French wooden storefronts were built by furniture makers, and suggest an interior, more private space.

- Using water to create intimacy or to create landmarks (« meet me by the fountain »).

- Introducing unexpected vistas or framed views - creating "nodes" as defined by Kevin Lynch, creating sublime moments as the smaller scale of a place suddenly opens up to a distant view. Allowing intimacy to accentuate sublime moments.

- Livening up outdoor rooms with public art, such as sculpture or murals (Gaudi's mosaic salamander guarding the steps to Guell Park in Barcelona is a wonderful example, playful as well as threatening).

- Creating places to sit, either alone or with friends (Christopher Alexander has many examples in "A Pattern Language")

- While running streets through projects is inevitable, this does not preclude carving out spatially modulated pedestrian-only spaces that can be perceived as outdoor rooms.

- Indoor public spaces (these include retail tenants as well as building lobbies) should be thought of as adding their own kind of variety to the public realm.

Conclusion: The Remembrance

of Things Past.

Image caption: on the left, a bowlful of Madeleines, the pastry that launched four thousand pages; on the right, 2 outdoor rooms evoked in Marcel Proust’s evoked in "Remembrance of Things past": his aunt's garden and the town square of Combray.

The most famous passage of "The Remembrance of Things Past", author Marcel Proust's epic reflection on the relationship between memories and past experiences, occurs when Proust bites into a Madeleine pastry dipped in herbal tea; the smell and taste he experiences suddenly give rise to the settings of his childhood: "once I had recognized the taste of the crumb of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-flowers which my aunt used to give me, immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like the scenery of a theatre to attach itself to the little pavilion, opening on to the garden, which had been built out behind it for my parents ; and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I was sent before luncheon, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine....” A whole series of places of different scales are evoked, starting with the intimacy of the childhood home, its garden, then the larger spaces of the town and finally the spaces of the open countryside. The madeleine may be the trigger, but what it brings forth is the interconnected spatial context, ranging in scale from intimate to vast, the repository of Proust’s childhood memories, his memory palace, which has shaped and organized his thoughts and reminiscences. The spatial context is the stage set in which Proust lives his life and which will fix his memories and allow him to tell his story. A construction in time (the narrative) is enabled by constructions in space (the settings of his childhood).

There is a little bit of Marcel Proust in all of us: after all, we all like to tell and share our stories, whether on Facebook, Instagram or during our social encounters. The places we move through (the rooms of our houses, our back yards, our stoops, classrooms, playgrounds, libraries, streets and public spaces) are like a giant filing cabinet of memories: these myriad places help us structure and organize the events of lives; they turn our fleeting experiences into a coherent narrative for our remembering selves to share with our friends and families. As architects and urban designers, we have a duty to shape and create these places in such a way that they can provide a home for our individual as well as our collective memories - we have a duty to be responsive to the workings and the needs of the human mind. To misquote Winston Churchill, "we shape our environments; thereafter they shape our memories".

______________________________________________________________

Further reading:

Joshua Foer: "Moonwalking with Einstein".

Colin Ellard: "You Are Here: Why We Can Find Our Way to the Moon but Get Lost in the Mall".

Alexandra Lange: "Meet me by the Fountain".

William Whyte: "The Social Life of Small Public Spaces".

Christopher Alexander: "A Pattern Language".

Daniel Kahneman: "Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow".