Creating Authenticity: It's in the Food!

Whatever the state of the economy, but especially when times are hard, our primal need for food turns into a search for comfort and delight. We anticipate food experiences, we recall potent dining memories, and we seek new and favorite old tastes, flavors, smells that provide experiences to satisfy us and to add to our arsenal of food-related memories.

Increasingly, it is our pursuit of health and delight that come together as we use food to reward ourselves. Not only should eating be pleasurable, but it should be healthful and socially responsible. We want to eat locally grown food if possible; it should be organic if possible and affordable; it should be grown without spoiling the earth or enslaving its growers; it should be delicious and non-fattening. We now impose a lot of requirements on this most basic of activities. But perhaps most important, the eating itself should be an experience. We are rediscovering that not only should we eat well, but that we should dine, and particularly in the company of others.

Smart developers constantly research trends and anticipate ways to cater to and profit from them. Developers who use food successfully focus on its local aspect. Place-specific cuisine is authentic and attractive. For example, San Francisco’s sourdough popularity has led to an explosion of artisan bread bakers, with parallels in the success of fresh produce, seafood, wine, cheese, coffee, tea and chocolate purveyors.

In addition, San Francisco’s diverse population has also led to the introduction of global cuisines to the area. The growth of diversity and more recently fusion in cuisines is a signal that the public yearns for satisfying experiences that reflect not only their own culture, but that of their neighbor’s as well. The lesson for developers is that food venues enliven our public spaces, enhance appeal, and sway us to extend our stays. Food’s role in public centers should be rediscovered as a frontier in place making.

There is a great contribution that food can make to retail places—adding to the authenticity that we’re all looking for. Near our office, for example, Westfield has created an unusual food court in its San Francisco Centre. It’s quirky, and it reflects the City’s diversity by featuring ethnic cuisines prepared by local chefs rather than national chains. Not far from where I live in the East Bay is the Pacific East Mall in Richmond, a large shopping center anchored by a Chinese supermarket chain. The mall has a handful of retail shops, but the main focus is Asian cuisine. Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Malaysian—you name it. There are sit-down restaurants, pad restaurants, and smaller casual dining venues. It’s a big draw for the local population. It’s almost always packed when I go there, especially on weekends, and it’s very family-oriented. A lot of Asian families spend a large part of their Saturday or Sunday there.

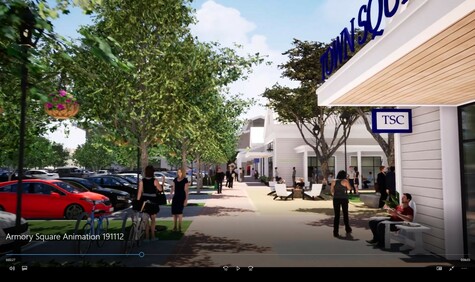

Because of the way retail development is financed, retail developers tend to sign up “credit tenants” with proven balance sheets, which usually translates into national chains. But this recession is affording an opportunity to try something different. There are enough vacant spaces available now that developers are trying alternative tenants, at least temporarily. Rather than limiting food to a single location , vacant spaces can be filled with casual dining, café, and gourmet food venues that make all-retail concourses more appealing and interesting. At one of our recently completed projects, the Otay Ranch Town Center, cafes and restaurants are scattered throughout the center as part of the leasing strategy. These tenants have performed well and result in a center with a continental flavor. Other alternatives to consider include incorporating gourmet and upscale grocery anchors as well as accommodating roving food trucks. The “taco truck” has morphed into a hot concept that works in urban areas, and one that could be incorporated into suburban mall settings as well. As we pull out of the recession, smart developers will understand the vital need to distinguish themselves from the competition. When all the regional malls in an area offer the same national restaurant chains, a little leasing creativity can result in a stand out success.

There are plenty of successful examples of places that thrive on the power of local, high-quality food—Pike Place Market in Seattle, for example, or San Francisco’s Ferry Building, or the Chelsea Market in New York. The Ferry Building opened during a recession, and emphasizing artisan food and restaurants became a way to distinguish it. The Chelsea Market is in a converted industrial building in New York’s meat packing district. It’s not pretty, and there aren’t any fashion stores, but it’s highly successful, with lots of fresh fish, meats, produce, plus bakeries and destination restaurants. I know people in Manhattan who go there almost every day. A similar venue, the French Market, opened last December in the commuter concourse of a major Chicago Metra station, and the initial reaction has been positive.

A city can support only one or two places like these, with that kind of concentration of local food vendors. But retail centers all over the country can use them as inspiration. If a center has a food court with 12 spaces, there ought to be a way to bring in a couple of tenants who are locals and whose food reflects the region.

The old ways of doing retail aren’t working anymore. Single-use places no longer serve our needs. To bring customers in, to give them reasons to stay and hang out, and to get them to come back, requires a variety of activities, new attractions and experiences that are worth our time. Offering food and dining that are fresh and different from the competition—that’s one way to succeed.