How Animation Changed My Design Approach

Architecture is a way of seeing things. That’s why digital visualization tools have been so impactful: not because they moved us from paper to the screen, but because they gave us more ways to see.

We used to design through elevations and floor plans. Then came SketchUp, which gave us the ability to model how people moved through the design, in three dimensions.

Now, animation allows us to design in four dimensions: through space and time.

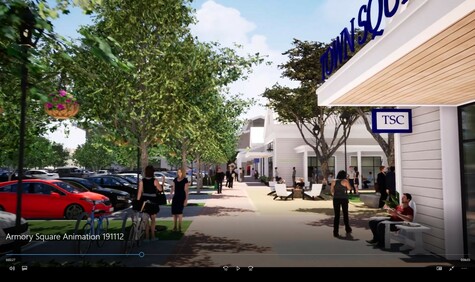

Field Paoli recently designed a concept for a shopping district in Calvert County, Maryland, called Armory Square. As part of the presentation to the County, we created an animation that expressed how people might use the space. As we went through this design experiment, I realized that animation has shifted how I personally think about design, as well as how we might engage stakeholders in the design.

Designing in Four Dimensions

The challenge with Armory Square was to design a town center for Calvert County. They had a plot of land that had previously held a junior high school and was now vacant. It’s a rural area, and driving is the main mode of transport.

We spent three or four years coming up with a plan that provided the kinds of retailing that could survive – which were larger stores, grocery anchored – in a format that related physically to what the County wanted: street-oriented retail, with grid arrangement so it had a small town feel.

To express the intent of the plan, Field Paoli suggested an animation. We hadn’t designed the project yet, so we had to create the architecture to populate the animation. You have to address things like benches and bike racks and light posts and plant species – it puts you a lot further along in design than you usually are at that point.

Then you add the people in – and that involves thinking about the social context. What do the demographics look like? What are people wearing? Are they families or groups of singles? Do they have pets? How are they using the outdoor areas? What’s the pedestrian experience like between the parking and the buildings?

Animation prompts you to figure out the experience before you’ve designed the buildings. In a sense that’s a continuation of a philosophy that we’ve always had at Field Paoli: that it’s the in-between spaces that create the feeling of place.

Architecture at the Human Level

By thinking about how people navigate the spaces in between, you see the project more thoroughly and realistically. You experience the project at the human level, not the “god-like” overview of the architect. It used to be that you’d design two or three beautiful views, or elevations, of the project, and there was the potential that, when it was built, people would walk around the corner and it might look terrible.

For Armory Square, we planned the masses of the buildings – almost like Monopoly buildings – and articulated them as we saw what the views were like throughout the animation. Basic massing is driven by functional requirements such as parking, economics, where the big buildings go versus the small buildings – it’s all programmatically driven. The grocery store wants to be in the most prominent location because you’re using it as the anchor; those sorts of principles.

From the human experience perspective, as you move through the animation, you begin to see where the more detailed visual interest makes sense. That led us to make decisions such as changing the grocery store gable because we realized it was too fussy. Then you start applying materials to the shapes, start pushing things around, and build up the landscape, all while animating.

You understand the scale. How the outdoor seating relates and supports the space. Where a mural on the grocery store exterior makes sense. Where a pianist might perform. All the elements that bring the experience alive. These are far from obvious on an architectural plan or even from a series of elevations.

The origin of the word “animate” is from the Latin verb animare, meaning “to give life to.” Architectural animation has the potential to breathe new life into what can sometimes be a static exercise – and enliven the feedback process at the same time. It should be a part of every conceptual planning project.