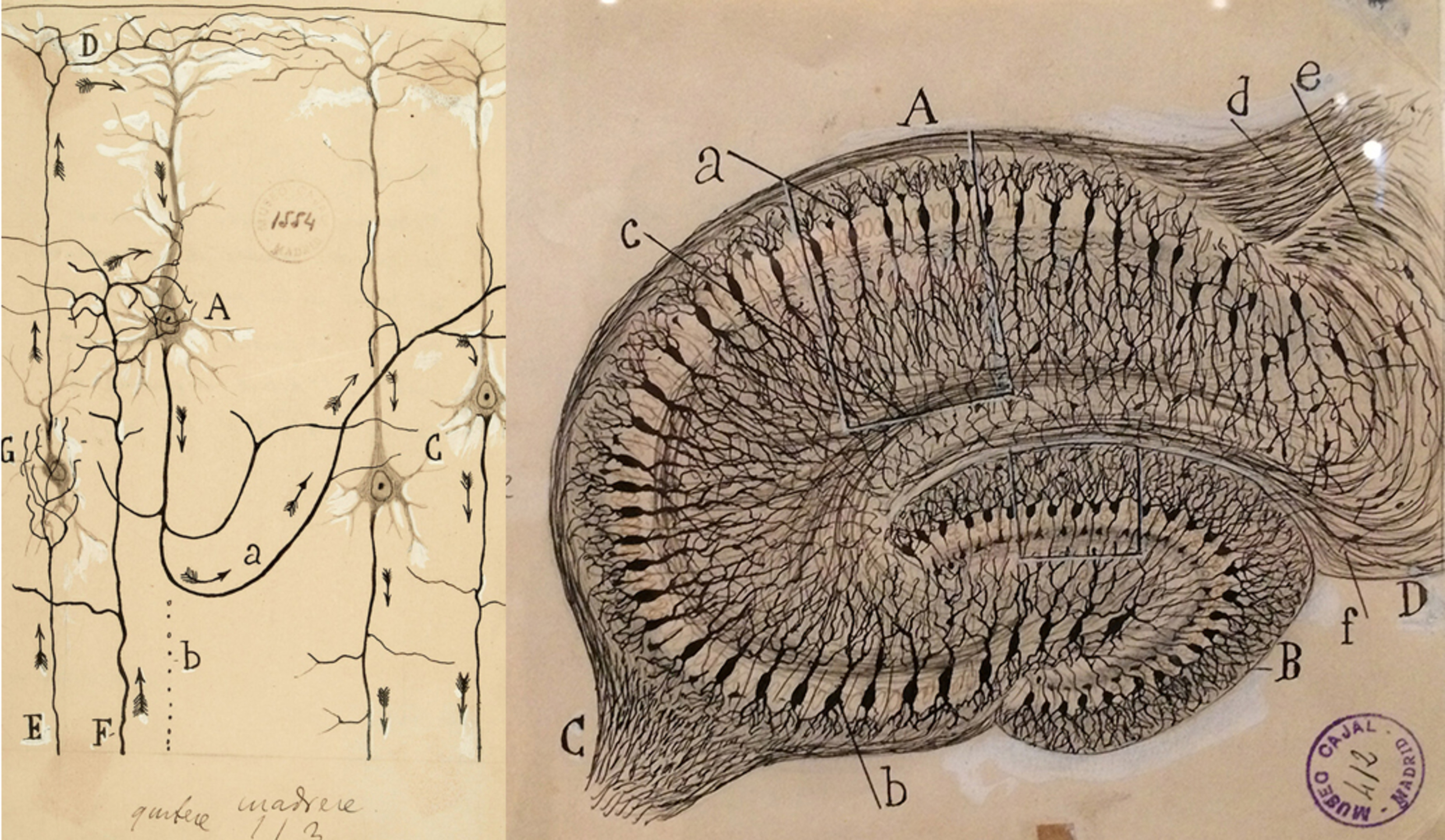

Two more Ramon Y Cajal drawings: on the left, a Study of pyramidal cells in the cerebral cortex in which Cajal proposes the directional flow of information; on the right, Cajal's drawing of a section through the hippocampus.

Memory Experiment #1: the Doorway Effect

We've all experienced the minor annoyance of leaving one room of our house and arriving in another only to realize we've forgotten what we went there to do. A team of researchers studying this phenomenon at the University of Notre Dame determined that walking through doorways actually contributes to forgetting - hence the "doorway effect".

This is an example of the encoding specificity principle at work: according to researchers our brain tends to compartmentalize memories from different environments and contexts; and if the brain thinks it is in a different context, then those memories belong in a different network of information. When we move from one room to another, the doorway represents the boundary between one context (such as the living room) and another (the kitchen). Event segmentation theory suggests that we use boundaries to help segment our experience into separate events, so we can more easily remember them later. These “event boundaries” also help define what might be important in one situation from what might be important in another. Hence, when a new event begins, we essentially flush out the information from the previous event because it might not be relevant anymore. This segregation actually gives us greater mnemonic capacity than if our brain was just one gigantic workspace where everything is connected. Our experience of the world is continuous and rich with information, and to manage this constant stream of information, we segment our experience into events, which are stored as episodic memory for later retrieval - pauses in the continuously unfolding narrative of our lives. Event segmentation theory hints at a deep relationship between how we structure the spaces and rooms we live in, and how we organize our lives: our spaces mirror the organization of our minds, and vice versa (as Winston Churchill eloquently put it, "we shape our buildings, thereafter they shape us"). The cost to our short-term memories is the very physical experience of forgetting items when we move between contexts, between compartments.

At first glance the doorway effect may appear to contradict the assumptions of the art of memory - as one walks through the various rooms of our memory palace, why are we remembering rather than forgetting? Here’s why: if you've just walked out of your living room into the kitchen and then forgotten why you did so, you could always walk back into the living room to see whether the setting will trigger the memory - or you could also just stay where you are, close your eyes and visualize yourself back in the living room - the forgotten memory may very well pop into your consciousness (as predicted by the encoding specificity principle, and as experienced by practitioners of the art of memory using the method of loci). The doorway effect is arguably more about how we remember than it is about how we forget: we don't remember isolated facts; instead, we remember things in context. A location, a setting gives context to a particular event; and context is a key aspect of making things memorable - in fact it turns out that we all have an inner context-creating organ that situates our memories within the vast inner networks created by our neurons: a small structure called the hippocampus, wrapped around our brain stem.

Mapping Spaces, Mapping

Memories

The "Knowledge" is what London's cabbies have to memorize over the course of up to four years of driving through the city's streets, memorizing its roadways, landmarks and destinations, and how get from one to the other. One noteworthy aspect about acquiring the knowledge is that the information does not "stick" if the learning is done from a car - participants have to be "in the space", hence the use of mopeds or motorcycles. It's as if they have to physically feel the space around them in order to memorize it, which can't be done from inside a vehicle.

According to Foer, brain scans of memory champions while performing memory exercises reveal that these activate the hippocampus, a small seahorse-shaped structure nestled around the brain stem, which is typically used for wayfinding - remembering how to get somewhere. Not only is the hippocampus related to place and memory - it may even have launched the science of neuroscience. In 1953, a man named Henry Gustav Molaison, of Hartford, Connecticut, lost his memory, the result of a surgical procedure designed to cure the debilitating epilepsy he had suffered since childhood, and involving the removal of most of his hippocampus. The procedure left him with no ability to store or retrieve memories of new experiences - after the operation he forgot all of his experiences within 30 seconds, but he retained a good deal of the texture of life he knew prior to surgery. For the first time scientists could associate a specific part of the brain with a specific function of the mind.

Eleanor Maguire, a neuroscientist at University College London, has spent 15 years studying the brains of London taxi drivers, and determined that their hippocampus was measurably larger compared to those of most people. This is because London cabbies not only engage in wayfinding on a day-to-day basis, but also spend three to four years learning “the knowledge”, an inner map of the whole city, its 25,000 streets and any business or landmark on them. The examination to become a London taxi driver is possibly the most difficult test in the world: test-takers have been asked to name the whereabouts of restaurants, flower stands, laundromats, and commemorative plaques, in a city of 9 million people and 600 square miles. Future cabbies spend upwards of 4 years riding around the streets of London on a moped or motorcycle, memorizing routes, landmarks and neighborhoods, as they internalize the whole city. By its very nature the knowledge of London cabbies is a contemporary use of the method of loci, associating a landmark with place; for a London cabbie the whole city is his memory palace - one that takes up to 4 years to build, and that he can readily visualize in his mind. Place and memory converge in the taxi driver's brain - just as place and memory converged to allow Simonides to recall the banquet participants.

The hippocampus plays a role in physical navigation and wayfinding by converting the linear routes we travel along into a spatially coherent mental map. As we explore new areas and travel along new routes, spatial information is used by the hippocampus to update our inner cognitive map. It seems that the hippocampus is a context-creating device, putting places and experiences in order, relating them to each other, fixing them by embedding them into the context of pre-existing places and experiences.

The hippocampus also helps us navigate through the landscape of our minds, turning short term memories into long term memories by activating neural networks that turn them into stories living in the cerebral cortex, awaiting later retrieval (the cortex is the outer layer of the brain, where billions of nerve cells reverberate via electrical and chemical impulses to retain and conjure up information). Re-living any part of that context can act as an involuntarily trigger for the memory - the encoding specificity principle at work.

Just as Foer commits a randomly shuffled deck of cards into memory by reorganizing it spatially as a series of scenes occurring in differentiated locales (effectively turning the deck into a story), so does place act on our minds in a similar way framing our episodic memories and allowing for their recall as we go through a walk (or a drive, in the case of a London cabbie) down memory lane. The contents of our minds are organized spatially, and the hippocampus is our own personal inner taxi driver, guiding us to various locales associated with specific memories.

Memory, Wayfinding and Identity

On the left, part of the "My country" series, by artists Damien and Yilpi Marks - a symbolic representation of an Australian tribal landscape, with symbols representing landscape features, food and water sources; on the right, a detail from Kevin Lynch's superimposed sketches of Boston as it is perceived by its inhabitants, indicating paths, nodes, boundaries and landmarks.

University of Toronto environmental psychologist Colin Ellard, author of "You Are Here: Why We Can Find Our Way to the Moon, but Get Lost in the Mall", suggests that the spatial memory skills exhibited by London taxi drivers as well as your average human being may have their roots in humankind’s ancient nomadic ancestry. In Australia and the American Southwest, Aborigines and Apache Indians independently invented forms of the loci method, but instead of using buildings, they relied on the local topography to plot their narratives and sang them across the landscape. Each hillock, boulder, and stream held a part of the story. Aboriginal songlines, by connecting different parts of the landscape into a creation narrative, help people to find their way from one sacred site to another, and finding your way meant re-enacting the creation stories of a particular tribe.

Ellard connects this ancestral wayfinding to the kind of urban wayfinding described are in Kevin Lynch's classic book "The Image of the city", in which Lynch observes how people perceive the contemporary urban environments where they live, organizing them as a series of paths, nodes, regions, boundaries and landmarks. Paths are linear routes used to travel from place to place; nodes are places of gathering; regions are the neighborhoods that make up a city; boundaries are the thresholds that define the edges of a place, and landmarks are local elements such as a corner bodega that can act as navigational aids. Together these elements form a virtual and emotional map, representing not the physical city, but the city as it is experienced in our minds - it's a mental map that overrides the quantitative, measurable physical aspect of urban environments and infuses them with a qualitative, hierarchical, and relatable content.

Psychologist

Barbara Tversky, author of "Mind in Motion", argues that our

minds are built on a foundation of cognition about place, space and movement

(which, according to Tversky, creeps into our language

with phrases such as “built on a foundation” and “creeps into”). On a pragmatic

level our brains started by helping us process our surroundings and the threats

and opportunities they presented; on a poetic level a very fundamental human

experience lies in the experience of the ever-changing world around us,

separated from the sky above by a horizon. Abstract thinking and poetic

thought are an adaptation of those basic spatial capacities.

Place and idea are related on a personal level too. Ellard relates the following anecdote: “I spent a portion of the writing time for this book living in a very small fishing village on the east coast of Canada, and I fell into the habit of taking long daily walks along deserted stretches of road, trail, or beach... The lapping waves, the crunch of stones or dry leaves underfoot, and the smell of salt and pine combined to produce an ineffable sense of place that became so strong that, like an Aborigine wandering the outback, I began to associate particular ideas with locations. From time to time, I would even revisit locations now resonant with my thoughts in order to clarify a concept or hash out a difficult ambiguity.”

It’s another example of the association of place and idea that was used by the art of memory - and an example of the encoding specificity theory, in which a place becomes associated with a specific set of ideas. This can happen both on a personal level (as in Ellard's example) and a societal level (the aboriginal songlines). And while the native populations in the United States had their own version of the songlines (and one of the tragic consequences of embedding narrative into the landscape is that when Native Americans had land taken from them by the USA government, they lost not only their home but their mythology as well), these have been replaced today by the quasi-mythical landscapes enshrined in our National Parks, with many making pilgrimages to the sculptures of Mt Rushmore, the geysers of Yellowstone, the granite of Yosemite, the canyons of Zion and the groves of Giant Sequoias in Southern California.

Memory Experiment

#2: the Baker/baker Paradox

A few of the pleasant (and memorable) associations evoked by the word “baker”

The "Baker/baker" paradox, another fascinating memory experiment, sheds additional light on the relationship between memories and the spatial and narrative context in which they are situated. Two groups of people are shown the the same photograph of a face; one group is told that the person's last name is Baker; the other group is told that the person is a baker. When the test subjects are re-tested a few days later, the group given the photo/occupation combination had a much higher recall rate than the group who had to remember the person’s last name. Same photograph, same word. Why would the group who was told the person's profession be much more likely to remember it than the group who was given their surname?Just as the key to memorizing a deck of cards is making a spatial story out of the pack, what is going on here is that when you hear that the man in the photo is a baker, that fact gets embedded in a whole network of associations: bakers cook bread, they wear big white hats, you can buy delicious treats from them. The name Baker, on the other hand, is tenuously attached only to the person’s face - and should that connection dissolve, the name will float off unanchored, never to return. The upper-case Baker has no meaning for us, whereas the lower-case baker does. According to Joshua Foer, memories are created when we voluntarily (or involuntarily in the case of the Baker/baker paradox) figure out how to take Bakers (the person's name) and turn them into lowercase “b” bakers (the occupation). It’s about taking information that is lacking in context, lacking in meaning and figuring out a way to transform it so that it becomes embedded in a web of pre-existing mental associations. It's about creating a mental map based on the information we are given.

Whereas the doorway effect hinted at the role of a spatial context, the Baker/baker paradox hints at the role of a narrative context; both build on and reinforce each other. Good memory is the same as good storytelling - making a story out of a series of events; and good storytelling situates these events in a well-defined spatial context. And at the end of the day, all of our memories are bound together in a web of associations - context is everything. For Joshua Foer, this is not merely a metaphor, but a reflection of the brain’s physical structure, made up of over 100 billion neurons, each of which can make upwards of five to ten thousand synaptic connections with other neurons. Foer describes these processes succinctly: “A memory, at the most fundamental physiological level, is a pattern of connections between those neurons. Every sensation that we remember, every thought that we think, transforms our brains by altering the connections within that vast network. Furthermore, the nonlinear associative nature of our brains makes it impossible for us to consciously search our memories in an orderly way. A memory only pops directly into consciousness if it is cued by some other thought or perception—some other node in the nearly limitless interconnected web. The spatial and narrative contextual networks at play in retaining memories mirror the neural networks that are activated in our minds. A neuron is nothing on its own, but in the context of the millions of other neurons in our brains it acquires immeasurable potency”.

The method of loci is so effective because the imaginary walk through a series of spaces combines a spatial context (the sequence of places) with a narrative context (the striking images). You are effectively turning a pack or cards into something as memorable as Homer's Odyssey or Tolkien's The Hobbit - a hero's journey (you are the hero) through a landscape of places framing striking encounters. The ancient memory palace echoes how our minds structure and organize information, and as we retrace our steps through our memory palaces the encoding specificity principle allows us to recall memories by conjuring up a place-based contextual web of associations.

The Experiencing Self and the Remembering Self

The power of place and memory seems to lie in their capacity to work together to organize experiences, and memories of these experiences, into a coherent narrative. Building on this idea, noted behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman, author of "Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow", suggests that we have two very different selves: an experiencing self and a remembering self, with both selves witnessing a very different version of events: what the experiencing self goes through is quickly supplanted by a remembering self that composes stories about of the experience and keeps them for future reference.

Kahneman argues that the frenetic picture-taking that takes place during our meals, social outings or holiday trips indicates that these are not necessarily moments to savor, but rather future memories to be documented, edited, and turned into stories - hence the popularity of Instagram, a ready-made way to share the stories of our lives. All those cameras pointed at the Mona Lisa are not there to record it - they are there to allow the onlooker to tell a future story about it.

According to Kahneman, we may think we are our experiencing selves, but in fact we are our remembering selves: they are the storytellers, building pictorial or verbal narratives based on our episodic memories. The remembering self composes stories and keeps them for future reference - the remembering self organizes our fragmentary experiences into coherent narratives. The remembering self is a product of the narrative and spatial context-creating hippocampus.

Today, the retail, travel and leisure industries are very much focused on providing experiences: whether it's the "Immersive Van Gogh Experience", or the proliferation of restaurants offering a "dining experience" rather than just plain old dinner, experiences have trumped material possessions to become the new status symbols, the new objects of desire. Despite all the hype surrounding experiences and the corresponding exhortations to "be in the moment", any self-respecting instagrammer will attest that the experience itself may be less important than how it ends up residing in our stories, to be shared with those around us in the immediate or distant future. Kahneman suggests that a vacation, for example, may be less about enjoying new experiences than helping us construct new stories and collect new memories for future broadcasting after some minor internal post-production editing. We are social beings at heart and sharing stories is an intrinsic part of our evolutionary make-up.

The places we recall play therefore an important part in how we relate to each other, as they allow us to first organize and then retrieve our thoughts - our inner filing cabinet (made up of neral networks) is a place-based system, that echoes the real physical places we experience. How well a particular place might help us retain memories has never been seen as a criterion for design - and yet not doing so seems to ignore a very fundamental way that we interact with our surroundings.

Part three of this essay, placemaking for the remembering self will look at how the above scientific insights might be applied to the creation of more memorable places.