What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter... a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue. I have always tried to hide my efforts and wished my works to have the light joyousness of springtime, which never lets anyone suspect the labors it has cost me....

—Henri Matisse

© Phil Bond | philbondphotography.com

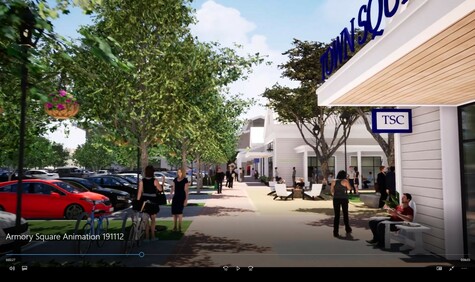

It is said that Millennials prefer to buy experiences rather than things; that they strive for authenticity and a sense of belonging. Based on these characteristics, a trip to the local mall is presumably not high on their to-do list; after all, the typical enclosed mall in the States has evolved to be a formula-driven machine for shopping, with a ubiquitous array of national tenants and department stores arranged around a stale-smelling food court — not exactly an uplifting environment in which to spend your precious time and hard-earned money looking for new experiences.

As a result of these shifts in consumer taste, the retail climate has shifted too, trending towards the creation of an experiential component with an emphasis on food and entertainment — or a combination of both (ax throwing and drinking, anyone?). Mexico City-based retail developer GICSA has even coined the term "malltertainment" to describe this evolution, characterized by visually intense environments that are more Vegas Strip than Ala Moana. Here in the States, established mega malls such as the Mall of America as well as newcomers such as American Dream Meadowlands are all relentlessly focused on developing their entertainment offerings. It's the Forum Shops or Fisherman's Wharf on steroids, and it's an approach that seems to work best in highly touristic destinations. The over-stimulation provided by these venues is not something that most people could handle on a daily or even weekly basis.

A Respite from Over-Stimulation

So is the future of retail a series of "look at me" projects for the new "look at me" generation? Or do Millennials (and others) welcome the occasional break from the pressures of Instagramming their life? When asked by Los Angeles-based Macerich to look at the renovation and expansion of Broadway Plaza, a one-level open-air mall located next to a historical downtown in Walnut Creek, California, we explored the idea of creating a respite from the over-stimulation we all experience on a daily basis. To quote Henri Matisse, we wanted to create a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.

© Phil Bond | philbondphotography.com

Macerich has owned Broadway Plaza since the mid 80's, at which time most of the buildings were remodeled and updated to a consistent palette of light beige stucco with teal and salmon pink accents — very much a product of its time. It is an open-air mall, anchored by Nordstrom and Macy's, and it directly abuts Walnut Creek's lively downtown, which has a charming small-town feel much appreciated by its citizens. Like many other traditional downtowns, it is characterized by an eclectic mix of one- to three-story buildings, with frontages in the 25′ to 50′ range. Although individually these buildings might be unremarkable, the scale and mix of expressions create a pleasant, walkable pedestrian environment.

As for the existing mall, it was primarily single story, with long, low buildings, some up to 400' long. Some minor incremental development and remodeling had taken place at the mall over the years, but the most significant change came in 2012, when Macerich opened a Neiman Marcus store at one end of the project and the City's General Plan was updated to allow up to 300,000 square feet of additional retail space at the project. Both Macerich and Macy's (who wanted to consolidate its operations from two buildings into a single expanded building) felt that the time was right to consider a significant redevelopment.

An early study scheme had identified that due to the density of the site and the presence of two underground culverts, the only way to add additional square footage was to go vertical — always a challenge for retail. The traditional enclosed mall, however, is a successful two-level prototype, and Macerich initially thought about creating a roofless version of this, similar to Santa Monica Place in Southern California. This approach caused some concern on behalf of the City, which worried that a two-level mall would turn in on itself and feel disconnected from the rest of the downtown.

© Phil Bond | philbondphotography.com

Integrating Mall and Downtown

Together with the Macerich design and development team, we decided to study an alternative approach: one that seamlessly integrated the mall into the surrounding downtown. Added square footage would consist of new ground-level space, new upper-level retail space, and new upper-level office space. An obsolete two-level parking deck would be demolished and replaced with a new four-level deck.

The big architectural gamble, however, was to allow tenants to design and build their own facades, which in our eyes was a win/win/win situation for the tenants, the City, and the developer. A win for the tenant since it allowed them to fully express their brand on their building facades, a win for the City because the visual rhythm of the resulting street frontage would ensure a change of expression every 30' to 50', echoing the street frontage found in the beloved traditional downtown, and a win for the developer because in theory we were streamlining the design approvals process. Of course, what works in theory doesn't necessarily work in practice, and the unforeseen hurdle was the City of Walnut Creek's request to see a full set of elevations before they could approve the project — a year before any leases were signed!

Our task was to convince the City that giving tenants relatively free rein as far as their facades (other than abiding by the comprehensive Macerich tenant design criteria) would not result in visual chaos. The key was communicating to the City that great outdoor spaces don't arise merely as a result of good facade design, they arise out of good urban design, and the urban design at Broadway Plaza is about as good as it gets. Based in part on the writings of classic urban design theorists such as Gordon Cullen (author of Townscape, first published in 1961) and Camillo Sitte (author of The Art of Building Cities, first published in 1889), the spaces between the buildings at Broadway Plaza consist of 14 distinct interconnected spaces (three segments of a vehicular street, five public gathering spaces, two broad pedestrian walkways, and four narrower pedestrian paseos) tightly defined by the buildings around them, not constrained by an orthogonal grid, which results in an ever varying and stimulating spatial experience as the visitor moves through the project. The longest of these spatial segments is 400', corresponding to a walkable block size; their width varies between 30' for the narrower paseos to 78' for the streets — again very intimate and comfortable dimensions. The variation in the scale and orientation of the outdoor spaces creates a range of visual, sensory, and auditory environments, which each have unique microclimates depending on weather and time of day. Complemented by lush landscaping and outdoor furnishings, it's an environment that invites strolling, lingering and relaxation: a soothing, calming influence on the mind, to quote Matisse. It's experiential retail, but understated experience. The almost organic nature of Broadway Plaza's spatial layout results in a seamless relationship to the adjacent historical downtown, to the point that you may not be aware of when you are entering Broadway Plaza. The mall has, in effect, become invisible.

Site plan showing how the project is integrated into its context.

Now retailers may be reluctant to openly admit this, but arguably one of the primary functions of retail design is to make you forget that you are shopping, so that perhaps you won't pay too much attention to how much you are spending. One approach to creating this forgetfulness is to create a sense of elation: this explains the success of experiential entertainment shopping. However, at the outdoor spaces of Broadway Plaza we adopted the opposite approach: relying on time-tested urban design principles to create a sense of comfort and well-being. The sales numbers speak to the success of this approach: within the first quarter of 2019, Broadway Plaza posted sales per square foot of approximately $2,000, up from a pre-redevelopment number of about $750 per square foot. It is currently 98.4 percent occupied, a significant achievement in this era of declining retail sales.

Experiential Urban Design

Designing the architectural equivalent of a good armchair that provides relaxation from physical fatigue may not be an architect's first response to a design problem, since we love designing heroic buildings and wow moments. But these do not necessarily make for good urban design, and good urban design is critical to creating environments that the public will enjoy not just during a single visit, but time and time again. In a room full of seating options, the public might be drawn to the cutting-edge chairs, but they will eventually settle into the comfortable armchairs.

Can traditional urban design principles be invoked to create the spatial equivalent of Matisse's armchair? An environment that appears effortless, one that does not call out at you loudly and brashly, but instead seduces you into a warm embrace, creating a sense of wellbeing that compels you to loosen your purse strings? At Broadway Plaza we’ve adopted a design attitude that I would describe as “experiential urban design:" paying attention to how customers will interact with the outdoor environment we’ve created; making sure that the scale, layout, variety and appearance of that environment will impact them in a positive, uplifting and enduring way.

The project’s success has been recognized by the retail industry: Broadway Plaza has won a top design and development award from the International Council of Shopping Centers, as well as an industry award recognizing its commitment to sustainability (the project is LEED Gold certified). Assisting Field Paoli on the project were the landscape architecture firm Studio Outside, the Civil Engineering firm Kimley Horn, structural engineers KPFF and the Environmental Graphic Design firm Redmond Schwartz Mark.