"Music is liquid architecture; architecture is frozen music."

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

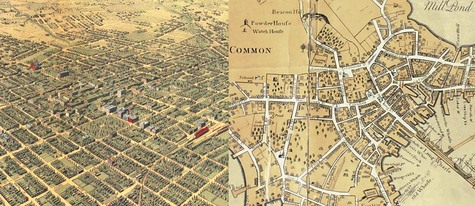

The Oculus, Santiago Calatrava's vast ribbed structure soaring above commuters and shoppers at the World Trade Center's Transportation Hub, is a wondrous sight to behold. Part gothic cathedral, part Victorian train station and part fantastical skeleton, the structure is symphonic in appearance, a striking embodiment of Goethe’s famous quote about architecture being frozen music. Walking into the Oculus feels like walking into a Beethoven symphony or a Wagnerian opera. The project generates plenty of traffic — more than a quarter of a million commuters daily and many millions of visitors annually. Retail sales, however, have been disappointing, and owner Unibail Rodamco Westfield is tweaking the tenant roster to find the right mix. The Oculus may be a beautiful and soaring structure, but it does not apparently make people feel like shopping.

Muzak, on the other hand, apparently does make people feel like shopping. As we enter the prime holiday shopping season, our retail destinations will fill our ears with the sounds of jingle bells jingling, little drummer boys drumming and pipers piping, in order to get us into that giving (and hence buying) holiday mood. But the musical aspects of retail environments are not confined to the holiday season: wander into your local supermarket at any time of the year, and chances are that a version of a song that was cutting edge back in the 60's, 70's, 80's or 90's will be playing in the background, blunted by a relaxed tempo and lush instrumentation, and turning your shopping cart into an imaginary dancing partner.

A Brief History of Muzak

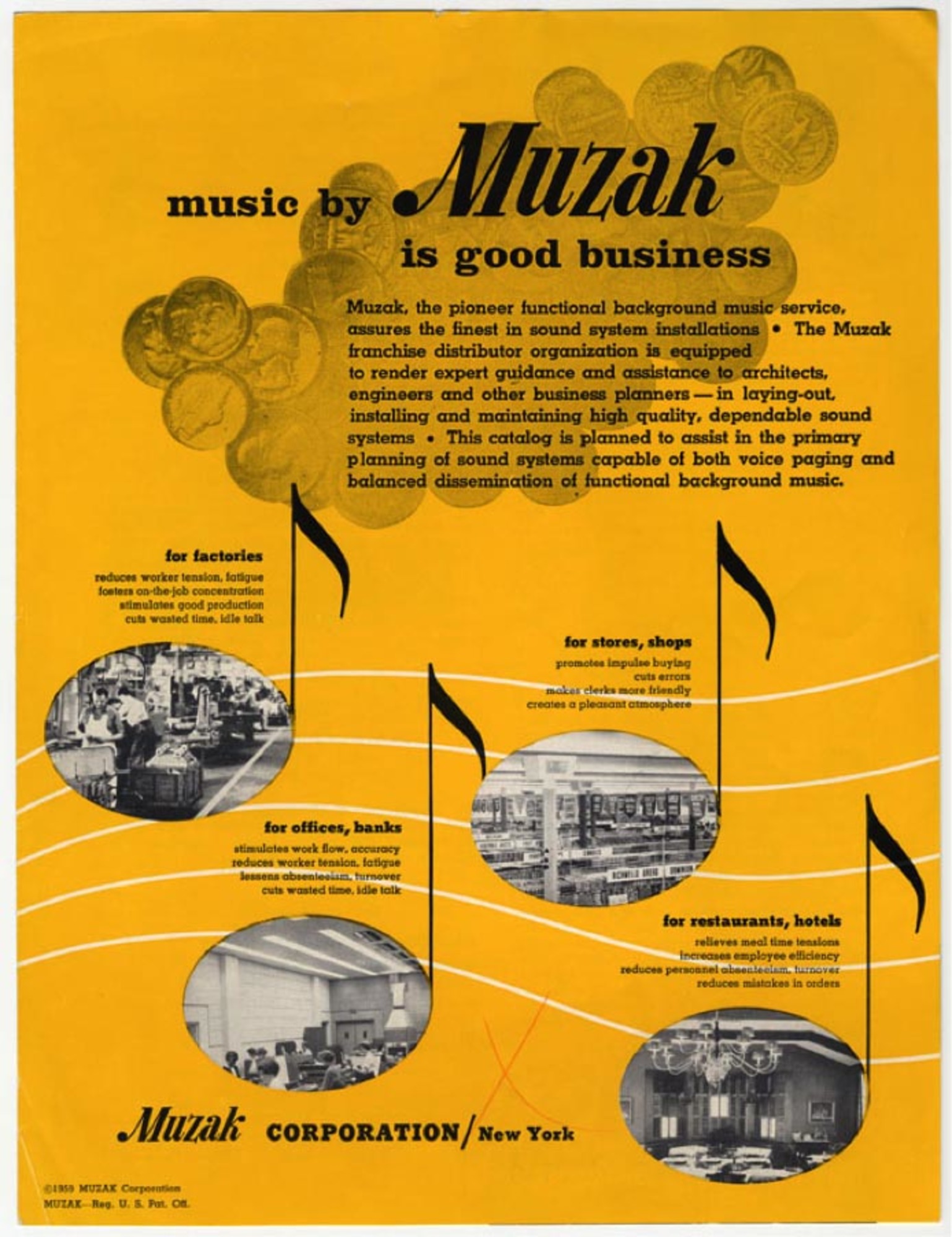

The brainchild of the eponymous Muzak company and initially conceived as a tool for increasing worker productivity, Muzak started as a subscription service piped through telephone lines in the late 20's and 30's, when radio technology was in its infancy and still unreliable (the Muzak company, originally called "Wired Radio," endures to this day as "Mood Media"). Corporations had realized that office workers needed a little boost first thing in the morning to get them going, and that this could be provided over the P.A. system: a bit of aural caffeine, which could gradually wind down as the morning wore on, with another burst of energy after lunch and a final one towards the end of the day. Just as Muzak could pep you up, it could also relax you, and so Muzak eventually expanded into hospitality and retail, first invading cocktail lounges (no doubt putting many a piano player out of a job), then restaurants, and finally making it into retail stores, grocery stores, and hotels. In 1953, Muzak reached the pinnacle of credibility: the White House was wired for it during Dwight Eisenhower’s administration. Lyndon Johnson was another presidential Muzak aficionado: he actually owned Muzak's Austin Franchise in the 50's.

Somewhere along the way Muzak became a derogatory term, plagued by accusations of mind control and soul destruction. Muzak was a notable feature of Aldous Huxley's dystopian "Brave New World," where happiness came at the expense of truth, and one of the Muzak Company's less savory clients was the Chicago Abattoirs, where the product was used to calm cattle being led to slaughter. According to rock musician Ted Nugent, "Muzak is an evil force in today's society, causing people to lapse into uncontrollable fits of blandness. It's been responsible for ruining some of the best minds of our generation." Nugent hated Muzak so much that he actually made a pitch to buy the company in order to liquidate it! Even if we don't despise Muzak with the same intensity as Ted Nugent, for most of us Muzak is to music what fast food is to the culinary arts: a rush to the lowest common denominator in a slavish attempt to please as many people as possible.

Muzak for all your needs!

From Avant-Garde to Armani and Ann Taylor

The birth of Muzak can paradoxically be traced to the early 20th century avant garde, who reacted against the Romantics' notion of "Art for Art's sake" and attempted to knock art off of its lofty pedestal. In an attempt to bridge the divide between "high art" and everyday life, painter Marcel Duchamp put a urinal in a museum, and composer Erik Satie created "musique d'ameublement" (furniture music), to be performed in cafes in short repetitive segments, designed specifically not to be listened to (Satie would actually become upset if cafe patrons stopped their conversations and started listening). Duchamp's aim was to provoke, but Satie's aim was to change the relationship between audience and music: he wanted to make the music part of a physical setting instead of something that was a focus of one's attention. Somewhere along the way furniture music turned into Muzak, and eventually found its physical embodiment in the cocktail lounges and hotel lobbies of the 50's. Frozen Muzak had finally arrived, not with a bang but with lush instrumentation and a Latin beat: interior design and musical ambience combined to tell you a story that would transport you to faraway places, complementing the Tiki bar and bottomless Mai Tais.The adoption of Muzak by retailers took a little longer: after all, the aim of a retailer is not to make you feel like you are in a dream-like state of bliss — they need you to make a few purchases. In a retail context, the story telling aspect of Muzak becomes important through the creation of an ambiance tailored to the psychographic profile of target customers. A Mood Media Muzak playlist creator interviewed by The New Yorker magazine describes the process: "Take Armani Exchange. Shoppers there are looking for clothes that are hip and chic and cool. They’re twenty-five to thirty-five years old, and they want something to wear to a party or a club, and as they shop they want to feel like they’re already there. So you make the store sound like the coolest bar in town. You think about that when you pick the songs, and you pay special attention to the sequencing, and then you cross-fade and beat-match and never break the momentum, because you want the program to sound like a d.j.’s mix. For Ann Taylor, you do something completely different. The Ann Taylor woman is conservative, not edgy, and she really couldn’t care less about segues. She wants everything bright and positive and optimistic and uplifting, so you avoid offensive themes and lyrics, and you think about Sting and Celine Dion, and you leave a tiny space between the songs or gradually fade out and fade in." The thought process is sophisticated, and it is not too difficult to see the correlation between the thinking of the Muzak curator and that of the interior designer: both are working to build a consistent and compelling story, one that the customer wants to become a part of by making a purchase.

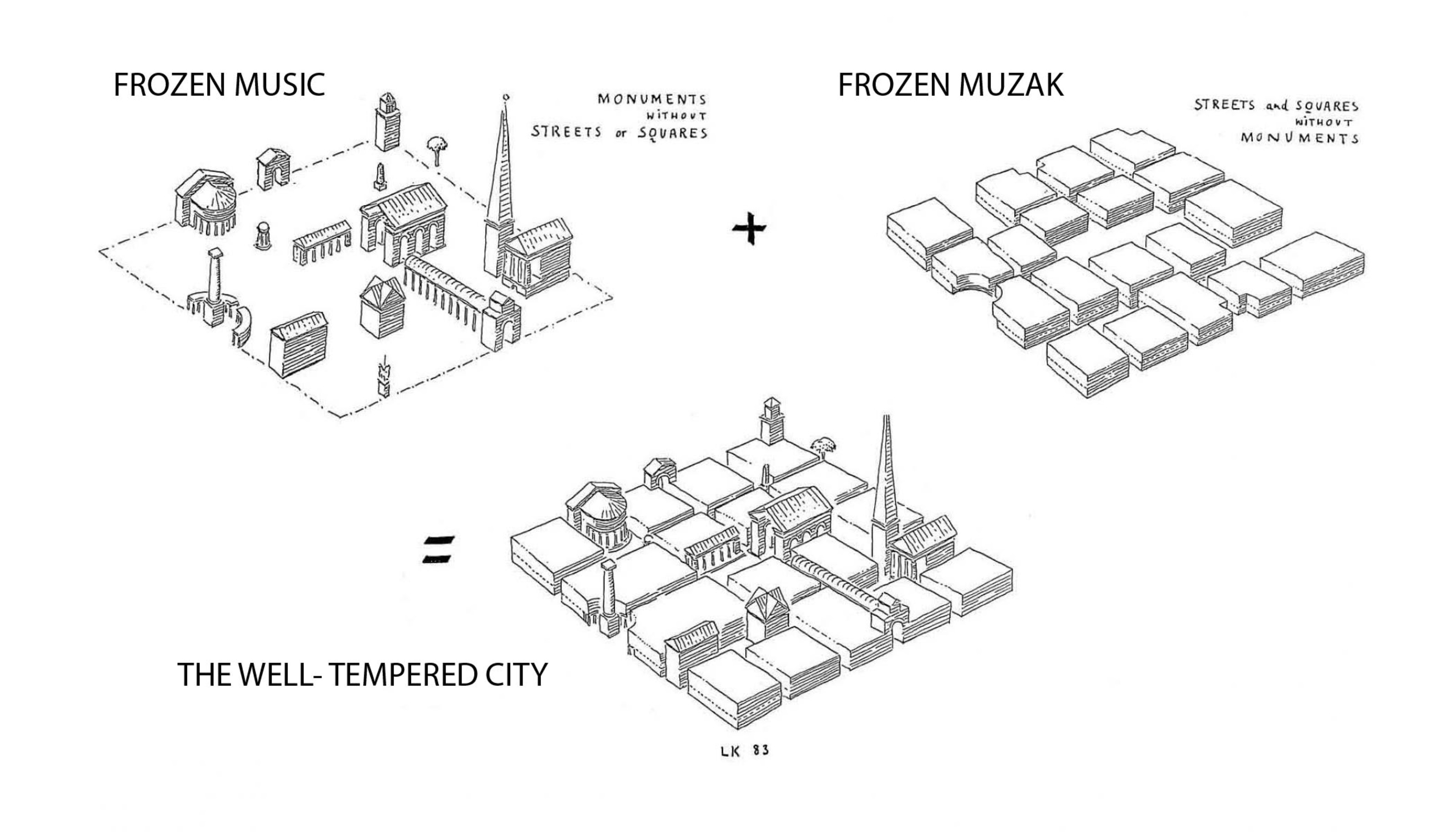

Frozen Muzak in the Built Environment

By creating a background ambience that enhances a brand and promotes merchandise, the Muzak curator and the interior designer think and design along similar lines. Should architects be expected to do the same? Buildings are innately resistant to being perceived as frozen Muzak: Goethe's adage rings true precisely because the history of architecture tends to be seen as a succession of heroic buildings: Greek temples, gothic cathedrals, neoclassical museums, or the creations of Le Corbusier, Mies, Kahn, and Calatrava. The focus is on purity and rigor: these buildings are proud and attention-grabbing objects, competing for our attention and competing with each other. They are designed to inspire awe rather than affection. Dramatic and monumental, they shun intimacy in favor of boldness.

To find Muzak in the built environment, we need to turn away from architecture and examine the work of the urban designer. Take for example Baron Eugene Haussmann, responsible for the huge transformations in Paris that took place in the 1800's. Much of Paris at that time was a warren of narrow streets, with little open space. Even grand buildings like Notre Dame and the Louvre were tightly hemmed in by houses. Haussmann decided to cut through the medieval fabric of the city and make the monumental buildings of Paris the nodes of a new network of boulevards lined with sidewalks and street trees (both rarities at the time), as well as buildings whose appearance was regulated by very strict design guidelines. They were all to be six stories tall, with ground floor retail, a short mezzanine above, a taller second floor with a continuous balcony, a third and fourth floor with Juliet balconies, a fifth floor with a continuous balcony and finally a mansard roof. The buildings are actually quite bland if you look at them for too long, but the whole point is that you are not supposed to: the boutiques and cafes lining the street capture the eye, with the upper stories floating above in a kind of comfortable anonymity. These repetitive buildings have become the backdrop to Parisian life as we know it, much as Satie's repetitive furniture music was created to be a backdrop to cafe society.

Making People Feel Like Shopping

Haussmann's background buildings allow the theater of urban life to unfold, creating a third place (to use sociologist Ray Oldenburg's terminology) for casual strolling, people-watching, and window shopping. The French call the combination of these activities "flânerie" (relaxed walking). Rather than being awed by Paris' architectural monuments, the flâneur is free to enjoy city life, comforted by the hospitable Muzak of the buildings around him. In Paris, shopping is not a chore: it becomes part the social experience of the neighborhood, with conversations to be had with merchants and neighbors at every turn. Shopping itself is the backdrop for socializing, the Muzak of casual social interactions.

By thinking of the city as a series of outdoor rooms punctuated by the occasional monumental building, Haussmann introduced a very legible and pedestrian-friendly hierarchy in the built environment. The formal activities of governance and organized religion live side-by-side with the informal activities of shopping and socializing, each defined by its own built forms, which coexist to create resonant social environments: a well-tempered city, to use developer Jonathan Rose's musical analogy. Other than the occasional civic building, the architecture is tightly controlled and subservient to the order of the street.

Frozen music + frozen Muzak = a well-tempered city (with apologies to Leon Krier)

The Rise of Retail Architecture

At about the time of the creation of the boulevards, new retail prototypes were emerging in Paris: the shopping arcade and the department store. With mass production increasing the availability of many goods, these new retail palaces were designed to accommodate the spending power of the emerging middle and upper-middle classes. The Galerie Vivienne and the Bon Marche in Paris; the Burlington Arcade and Harrods in London; and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in Milan were the new cathedrals of commerce, the progenitors of the shopping malls that were to proliferate across the United States. These were very successful shopping destinations, designed by architects rather than urban designers, with the goal of elevating the shopping experience. But if the shopping experience becomes too elevated and too separated from its urban context, does it prevent us from engaging in the more casual social activities traditionally built around shopping? Retail architects have long debated whether malls should be statement-making buildings or should somehow recede into the background; at the Oculus, it was all about making a statement.

Don't be Afraid of Frozen Muzak

It is perhaps time to drop the "Muzak" moniker, with its negative connotations, and to talk of background music instead - with a role similar to that of the movie soundtrack. Projects that emphasize placemaking such as Country Club Plaza, Easton Town Center and Victoria Gardens all feature carefully crafted outdoor spaces defined by background buildings. The setting is enlivened by "foreground" elements such as retail storefronts, a fountain perhaps, or a key retail anchor such as the Apple Store at Broadway Plaza near San Francisco, a pristine object surrounded by a more traditional building fabric.

Object and context: the public fountain at Broadway Plaza

Create Social!

At the end of the day Muzak found its true calling not as a tool to increase worker productivity, but as a social lubricant. In this age of e-commerce, can we expect the same from the physical settings which we frequent? Mood Media's curators create a synergy between the shopper and the store environment; can retail architects create a similar synergy between the shopper and the built environment? We may very well be at a turning point where the continuing relevance and appeal of today's malls will depend on a wave of the urban designer's wand in order to transform these cathedrals of commerce into richer urban environments, so that shopping can be reconnected to the casual, pleasurable and rewarding social activities that form the Muzak of our lives.

If you find yourself in need of a little Muzak, here is a link to Mood Media's website.

Mood Media calls their playlist creators "audio architects" ̶ who knows, even Goethe might have approved!