Neuro-placemaking: Three Reasons Why We’re Neurologically Predisposed to Love Parisian Cafes

Yann TaylorThe first of an occasional series of posts on the relationship between evolutionary biology, neuroscience, behavioral economics and the art of placemaking.

The scene is familiar: individuals, couples or small groups of people relaxing at sidewalk café tables, enjoying food, gazing at the passersby. Just about any project presented to a planning commission includes this scene in a rendering. The architecture may differ, but the situation remains the same. The sight of people communing in a welcoming urban environment sends the message that this will be a successful project.

Why are we wired as human beings to find this scene so appealing?

1: Smell the Coffee

Most four-legged mammals rely heavily on their sense of smell to understand what is going on around them. Humans are different: since we evolved to stand on our two hind legs, our noses moved away from the ground and we learned to prefer our eyes and ears.

Nevertheless, the olfactory sense is unique in all our senses in that it has a direct connection to the cortex (the "higher" part of the brain) and to the amygdala and the limbic system (a group of structures that play a key role in processing our emotions and episodic memories—structures which for a long time were referred to as the "rhinencephalon," meaning "nose brain").

One of the key structures of the limbic system is the hippocampus, which is critical to the formation of long-term memories. The sense of smell has privileged access to the hippocampus: it is one synapse away from the olfactory bulb. Both spatial and olfactory information help "fix" long-term memories within the hippocampus. (By contrast, other senses—vision, hearing and touch—have to go through a circuitous neural path before they get to the hippocampus.)

That is why odors can act as intense triggers for memories and emotions—and the aroma of coffee is no exception. The roasting process alters the structure of the chemical compounds in coffee, creating caramelization and bringing out a unique aroma that combines a number of attractive scents, including sweet, spicy, fruity, floral, and smoky. The smell of coffee becomes a powerful reminder of the social settings where we have consumed this beverage; in my case it evokes summer mornings in my grandparents’ house, where drinking a bowl of cafe au lait was part of the ritual of waking up.

2. Prospect and Refuge

Open your Kindle app and you will be greeted with the silhouetted image of a person sitting under a tree and reading a book. The tree appears to be located on a gentle hillock, presumably affording views of the surrounding area. The image is compelling because it evokes the idea of prospect and refuge—a safe and comfortable spatial configuration in which an intimate space (a refuge) is provided with a vista of the surroundings (a prospect).

English academic Jay Appleton developed this theory in 1975 in his book The Experience of Landscape, proposing that we still possess a primal connection with the environments that shaped our species, particularly ones that allowed us to be hunter rather than prey. Some of the great icons of modern residential architecture echo this spatial quality: Mies Van Der Rohe's Farnsworth House, for example, a jewel box raised a few feet off the ground to give vistas of the surrounding countryside; and Le Corbusier's Villa Savoie, raised on its pilotis with horizontal windows enabling one to scan the distant horizon.

The principle applies to urban locations as well: in

most public spaces, people will tend to sit and relax at the edges rather than

the center—think of where you'd rather

have your al fresco lunch. Some people may want to see and be seen, but

most people will prefer to see rather than to be looked at. In The Great

Good Place, the book that launched the idea of the "Third Place"

(and greatly influenced Starbuck's Howard Schultz), author Ray Oldenburg

extols the virtues of the French cafe, and in particular the terrace,

that indoor/outdoor space set back from, and looking out onto, the adjacent street. The terrace is a

great example of prospect and refuge: a comfortable place from which to watch

the world go by—an urban front porch of sorts.

3. Peripersonal Space and Extrapersonal Space

Peripersonal space and extrapersonal space are two neurological concepts that describe a fundamental way we process our surroundings. The realm of peripersonal space is that which immediately surrounds the body and is within easy grasping reach; anything beyond is considered to be part of extrapersonal space, extending far off into the distance.

We are wired to experience our surroundings as these two distinct realms, often separated by a horizon line: peripersonal space lies mostly below the horizon line of gaze, and extrapersonal space typically lies above the horizon line. Peripersonal space will trigger multi-sensual input (touch, smell, vision, hearing) and primarily engages the limbic system (memories, desires, fight or flight reflexes), whereas extrapersonal space, primarily visual in nature, engages the neocortex and its focus on future planning (and more rational forms of thinking).

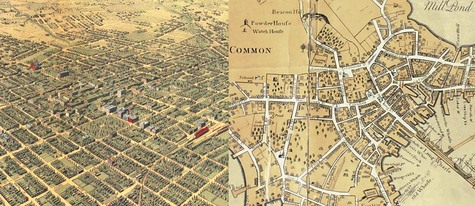

The two realms are typically divided by the horizon line. Observe the building in the photo below and note how there is a strong horizon line

separating the ground and upper floors. The ground floor (peripersonal

space) has a visual fine grain to it, texture, color, depth and activity.

The upper floors, typical of many Parisian buildings from the Haussman era, are

more regular and repetitive, with simple rhythmic fenestration, a monochromatic

color palette, and clarity of expression. The contrast between a rich

peripersonal space and a simplified extrapersonal space creates a strong

experiential resonance between onlooker and building: it is as if the building

is echoing how we are wired to perceive our surroundings. This subliminal

echo no doubt contributes to the appeal of the setting.

Understanding how we interact with the environments that surround us is of fundamental importance if we are expected to design welcoming environments

Designing Welcoming Environments

Understanding how we interact with the environments that surround us is of fundamental importance if we are expected to design welcoming environments. In many ways, creating a welcoming building or setting can be more challenging than creating a building designed to provoke. Provocation is easy; understanding how spaces impact us sympathetically on a deep emotional level is more difficult.

Of course, as architects we do not control all the elements that will create positive memories of place. For example, when a surly waiter suddenly enters our peripersonal space (assuming, that is, that we have been able to get his attention) and barks something at us in a language that we do not fully understand, it will likely cause our amygdala to send a distress signal to the hypothalamus, which will activate the sympathetic nervous system by sending signals through the autonomic nerves to the adrenal glands, pumping adrenaline into the bloodstream. Pulse rate and blood pressure will go up—our “fight/flight/freeze” stress response has been activated! Perhaps a local might fight, but as tourists we will likely freeze in the hope of defusing the waiter’s aggression (after all, playing possum does occasionally work as a survival mechanism), bemoaning the fact that French waiters are not dependent on good tips to make a living.

For more on scent's role in creating welcoming places, read Scent: The Forgotten Storyteller in the Retail Environment.