Towards a more experiential approach to mall redevelopment

“We say the cows laid out Boston. Well, there are worse surveyors.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Wealth"

- Is the rush towards transforming malls into "urban" mixed-use destinations happening at the expense of good placemaking?

- While a younger post-college demographic may be drawn to denser urban environments, those graduating from that demographic (and getting married and having children) may prefer a "surban village" to an urban district.

- They may be looking for something more intimate, more convenient, safer and healthier than an urban district. Paying attention to the preferences of this demographic will be an important part of the success of tomorrow’s mixed-use destinations.

- A common redevelopment strategy is to create an urban feel by laying out an orthogonal grid of streets punching through the mall and connecting it to its surroundings. By focusing on the grid as planning solution, are we ignoring other design strategies that may better resonate with our target demographic?

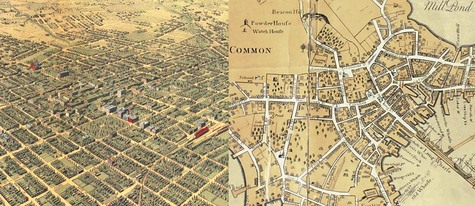

- The two images above (on the left, San Jose in 1901, and on the right, Boston in 1777) illustrate two fundamentally different approaches to urban design. San Jose's layout is based on the orthogonal grid, a design strategy originally developed by roman military planners, imported to the Americas by the Spanish Empire and codified in the "Laws of the Indies". On the other hand the original Colonial towns were villages characterized by a street layout that balanced human needs with the constraints and opportunities of the surrounding landscape - resulting in a more intimate, grounded and unfolding experience.

- Is it time to think outside the grid in order to create a more experiential approach to mall redevelopment?

Urban versus suburban versus something in between

Do millenials and empty nesters prefer the city or the suburbs? A recent Wall Street Journal article suggests that millenials, gen-xers and baby boomers are turning their backs on the cities AND the suburbs and looking at alternative environments that might combine the best of both worlds: intimate scale, walkability, a reasonable commute, and cultural and recreational amenities: an urban village. Current demographic trends coupled with the challenges faced by the shopping center industry could be a key part of the emergence of this new kind of "surban" environment, with the anticipation that some of our struggling malls could be redeveloped into nodes that act as shopping destinations as well as desirable neighborhoods. Is it however enough to take the roof off the mall, impose a street grid on the site and fill it with mid-rise buildings, or do we need to think about other design strategies that would maintain the relaxed feel of many successful suburban retail destinations? When does urban become too urban?

How medieval towns influenced shopping

mall design

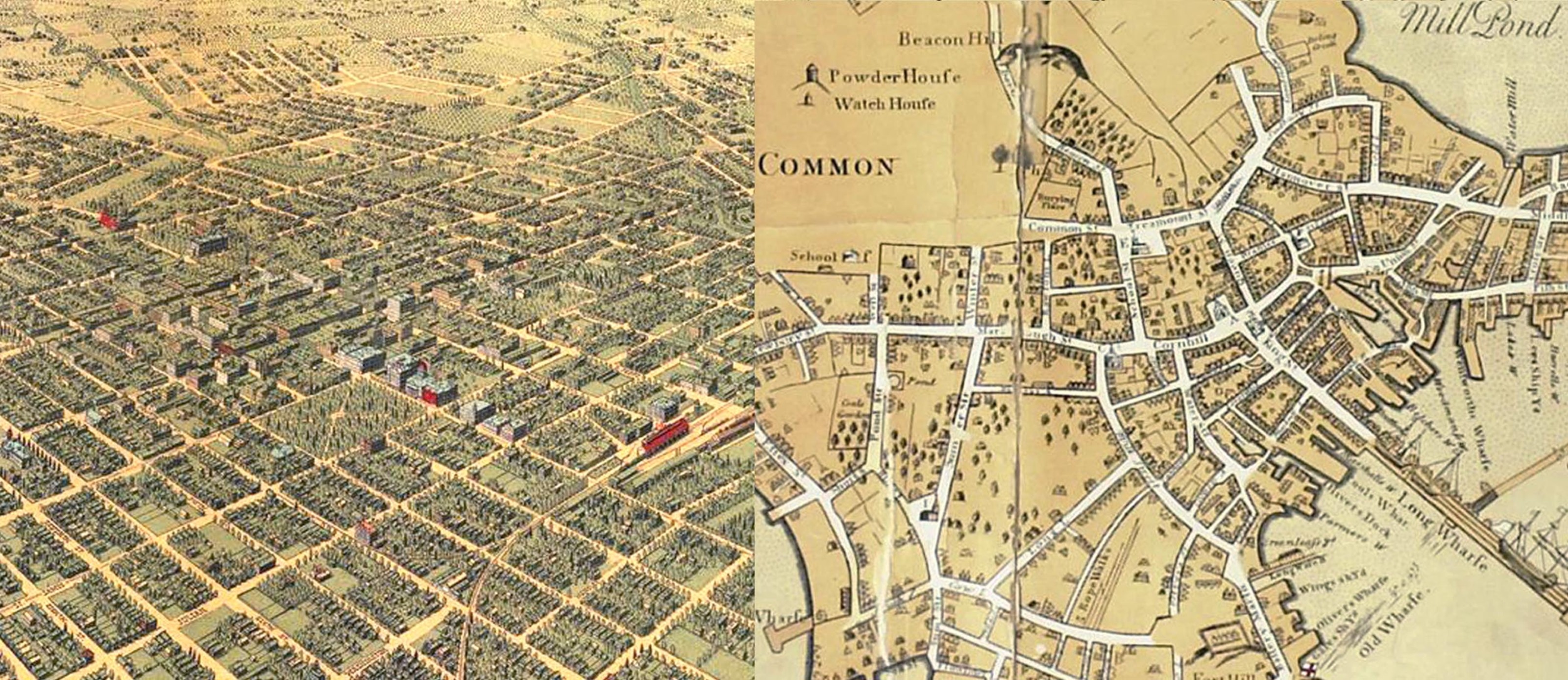

Fortress mall and fortress town - left: Aventura Mall, Florida, c. 2008, right: Orvieto, Italy, c.1898 ; right. Both have some key elements in common - they create a strong sense of center ; they have a strongly defined boundary (the city walls in the case of Orvieto, the mall loop road in the case of the Aventura Mall), and they provide an intimate meandering pedestrian experience. Churches, monasteries and cultural buildings anchor Orvieto, and of course the department stores have traditionally anchored malls. Both Aventura and Orvieto attract thousands of people each year

During the 80's many architects gained a renewed appreciation for architectural history, went to Europe for inspiration and discovered the pleasures of the meandering layouts of medieval towns. The search for that elusive "sense of place" had begun, as retail architects and developers, looking for ways to improve on the first generation of pedestrian-focused, Victor Gruen-inspired Shopping Malls, began to introduce more interesting layouts into mall common areas. The Aventura Mall, designed in the early 80's, is typical of many projects built across the United States, with a perimeter defined by a loop road and an internal layout that feels much less rigid than the malls of the 60's and 70's. The mall is designed to encourage exploration, to create a more relaxed pace of shopping and to prolong linger time. Both mall and hill town were inward-looking environments, focused around an organic pedestrian spine - an approach exemplified in California with the open-air work of John Field (founder of Field Paoli) in projects like Paseo Nuevo in Santa Barbara, but an approach which also generated hyperactive projects such as Jon Jerde's Horton Plaza in San Diego.

The grid makes a comeback

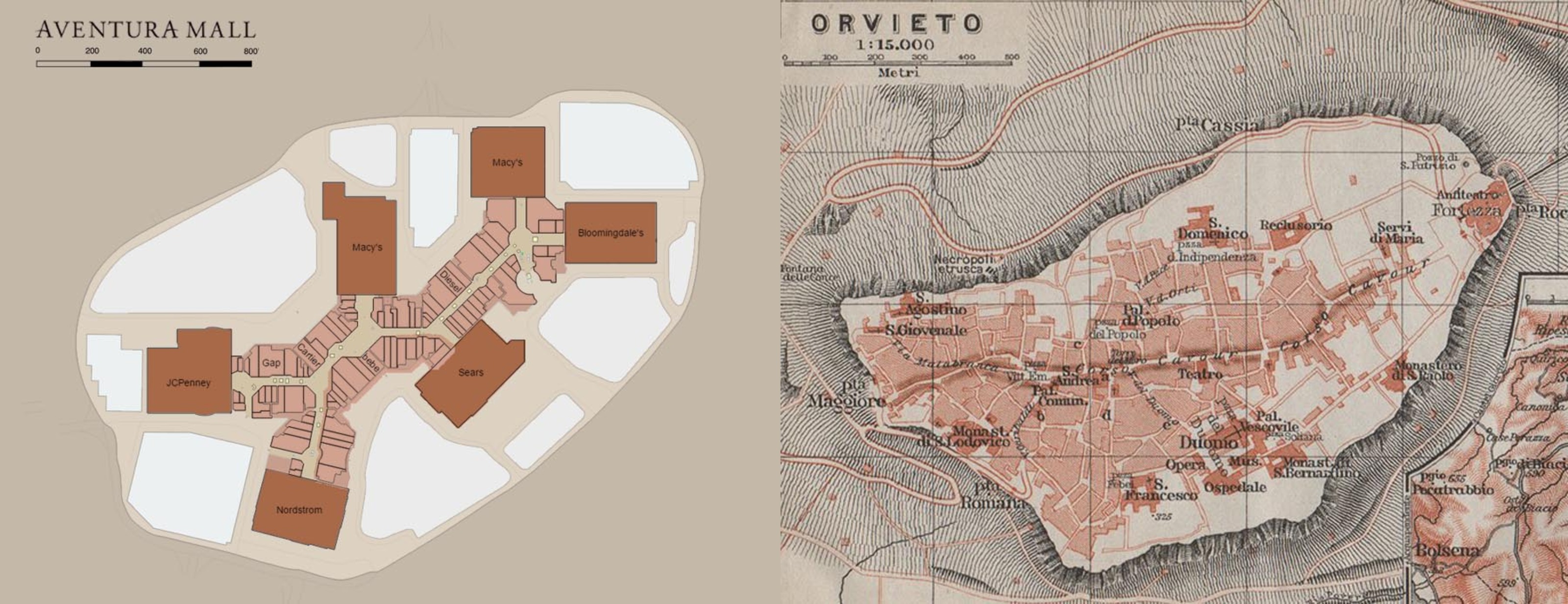

Left: Steiner and Associates' Easton town center, by M+A Architects, which opened in 1999. Right: Forest City's Victoria Gardens, masterplanned by Field Paoli, which opened in 2004. Both projects introduce the liveliness of city streets into the retail layout; a network of public pedestrian spaces is nevertheless maintained in order to provide a counterpoint to the vehicular streets.

Lack of connectivity to its surroundings may

be an asset for a fortress city like Orvieto but it has its drawbacks for a

mall, which by turning its back onto the surrounding area presents a very

unappealing first impression to its customers. In the 90's the New

Urbanism movement led a revolt against the cellular nature of suburbia, with its

endless cul-de-sacs and isolated destinations. New Urbanists emphasized the need to find ways to better connect the fragmented pieces of the

suburban landscape. The grid was their answer, and the next big shift in

regional mall design came in the 90's and 2000's with the advent of Main Street

Retail and open-air regional malls designed like gridded towns rather than

stand-alone buildings. The internal wandering paths of the 80's

malls were replaced by vehicular streets with on-street parking: the premise

was that the suburban shopper was regretting their divorce from the liveliness

of downtown, and that creating an environment reminiscent of America's small

towns would bring a sense of urban vitality into the suburban

environment.

A short history of the grid

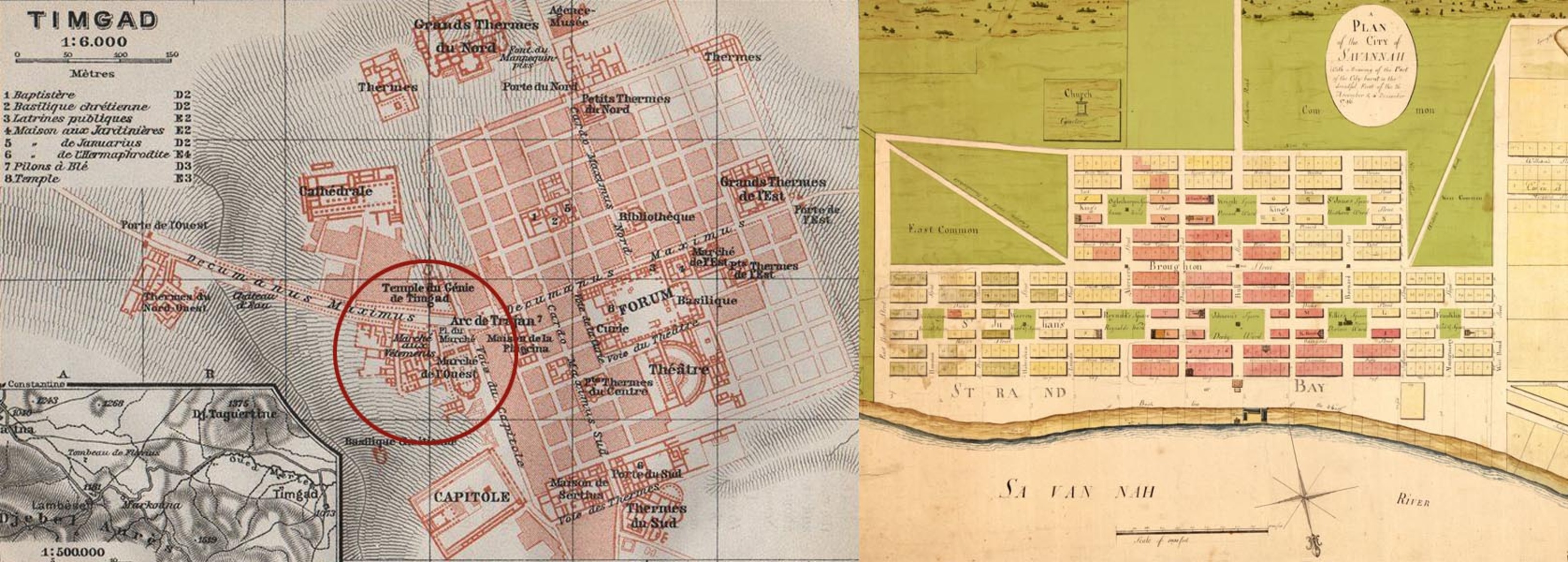

Left: the Roman town of Timgad, one of the best preserved examples of the Roman Military grid. Interestingly the town's market (circled in red) sat uneasily in the rigidity of the grid and eventually migrated away from the forum towards the edge of town where it could grow organically. Right: one of the more famous gridded layouts in the US is Oglethorpe's plan for Savannah - although it took interrupting and disrupting the grid with open spaces to create such an inviting environment.

The most notable early use of the grid as a

planning device was by the roman military. The grid represented the imposition

of Roman imperial order onto the "barbarians" they conquered. History repeated itself 1500 years later with the

Conquistadores and the imposition of Spanish imperial order (by way of the

"Laws of the Indies") onto their newly acquired American dominions - an order symbolised by gridded town layouts. Philadelphia

is generally understood to have been the first example of the grid in the US,

and order was certainly on William Penn's mind when he laid out the his grid in the late 1600's. Penn argued that its use would avoid the overcrowding, fire

and disease that he had witnessed in London - and it also happened to be a convenient way of

subdividing his land and selling off parcels. Approximately 50 years after

Penn laid out Philly, Oglethorpe created his plan

for Savannah, in which the grid is disrupted by a series of green public

squares. The creativity displayed by Oglethorpe was

unfortunately not inherited by 19th Century Railroad surveyors as they

mapped the new towns created during the westward expansion of the United

States, and the grid eventually became the de facto approach to

town planning - not so much to avoid the ills Penn warned about, but because it allowed for the rapid subdivision and

auction of large parcels of land. In addition to being

a symbol of civilizing order in the context of the Wild West, the grid was now

a symbol of commercial expediency. Railroad

surveyors did not care much for placemaking, and Ralph Waldo Emerson's

unkind words about surveyors reflected his dislike for their purely utilitarian

approach.

Gridded plan versus cellular plan, urban versus village, consumer versus guest

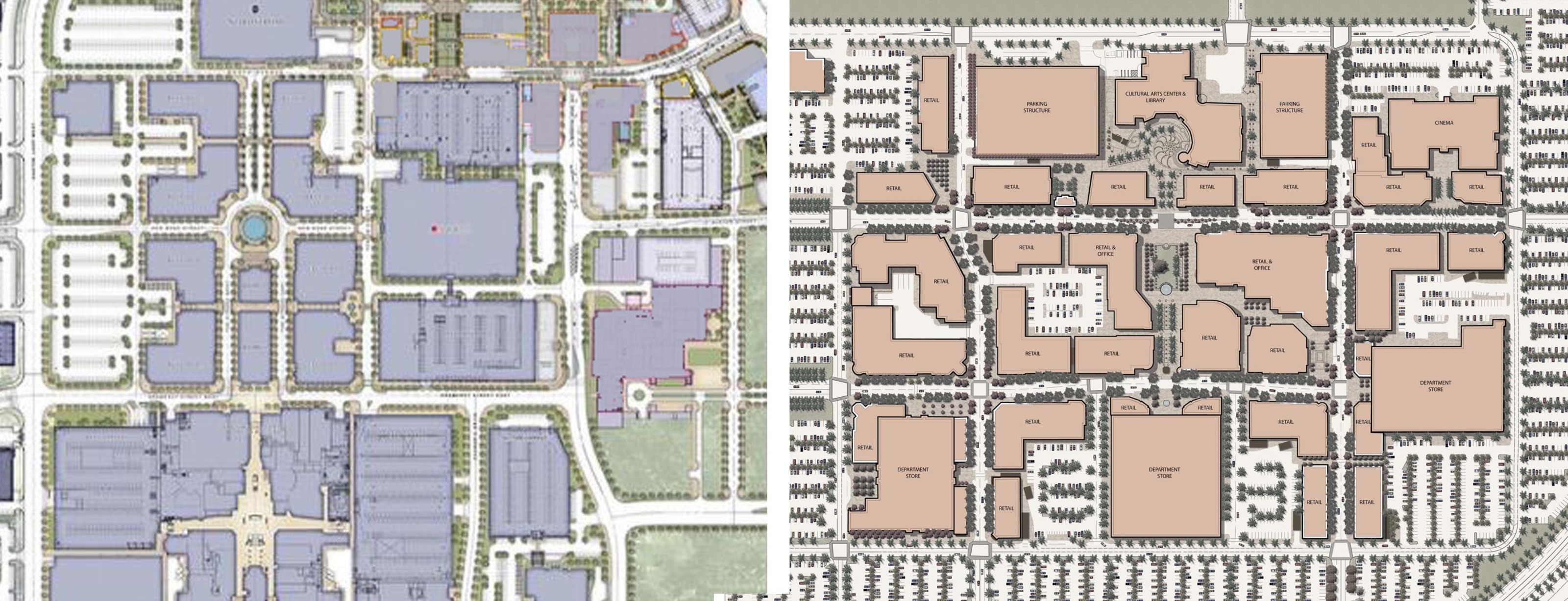

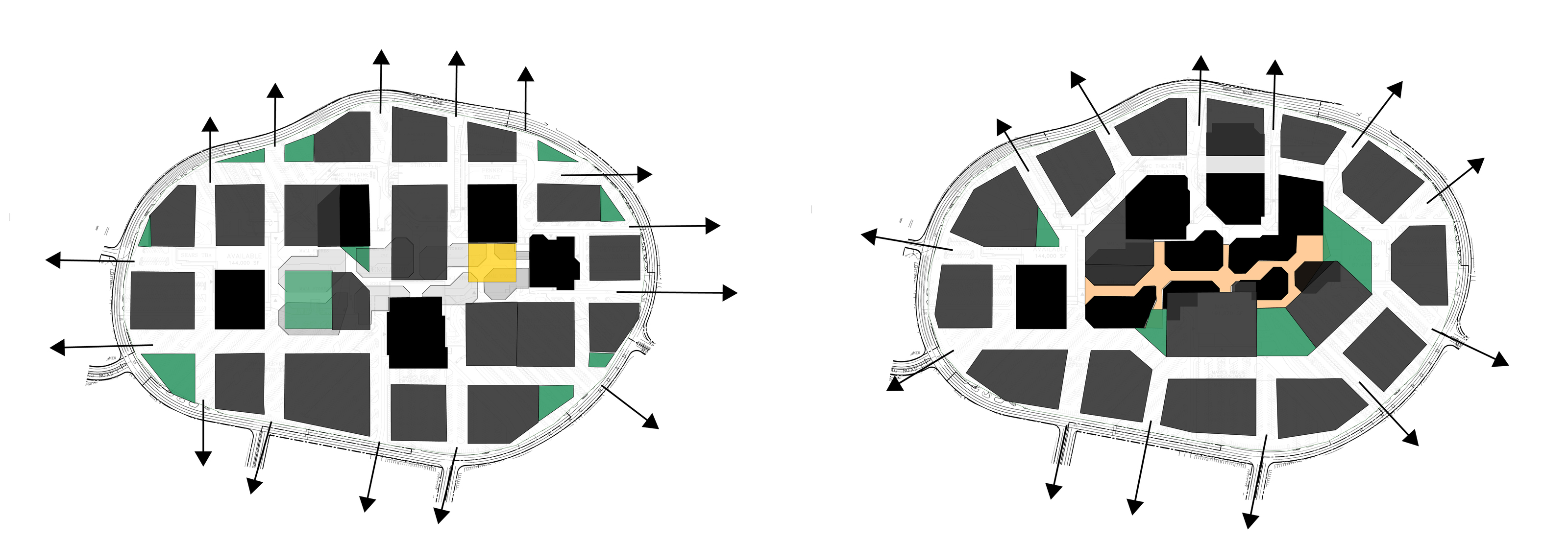

"De-malling" diagrams: left: using a grid; right: using a cellular layout. With a grid, blocks need to be omitted to create public spaces and a sense of place, and the pre-existing loop road geometry creates numerous awkwardly shaped leftover spaces at the perimeter; with the cell, the street layout itself creates the sense of place, and leftover spaces gravitate towards the middle of the project and contribute to the variety of open spaces. The urban grid reflects the rhythm of the automobile; the village cell reflects the rhythm of the pedestrian.

The grid and the more centralized, organic cellular plan found in places like Orvieto and

colonial Boston each lead to very different outcomes in terms of sense of

place and space. The grid feels urban, more impersonal, the result of top down

planning with a focus on efficiency and connectivity; cellular layouts

are village-like, centralized, organic, intimate, and biophilic in nature. A

walk through a gridded city is very different from a walk through a set of

meandering village streets: the grid does not encourage lingering, whereas a

cellular layout feels more inviting and spatially textured. If we are to

make the distinction between the transactional consumer (one who purchases

commodities, and who looks for value and convenience) and the social customer/guest (one who purchases discretionary items, and who looks for emotional

connectivity and experience), then the efficiency of the gridded city and

its suburban cousin, the strip mall, would best serve the transactional

customer; the social customer on the other hand will respond more to the

warmth and intimacy of the cellular village. Urban is about getting things

done; village implies a more relaxed pace. The urban grid appeals to the mind,

whereas the cellular village appeals to the heart. The urban grid also

appeals to the controlling tendencies of many architects and urban designers who view suburbia the same way that the Romans and Conquistadores viewed their

newly conquered lands - a disordered landscape that needs to be tamed.

In this era of disruptions, let's

disrupt the grid

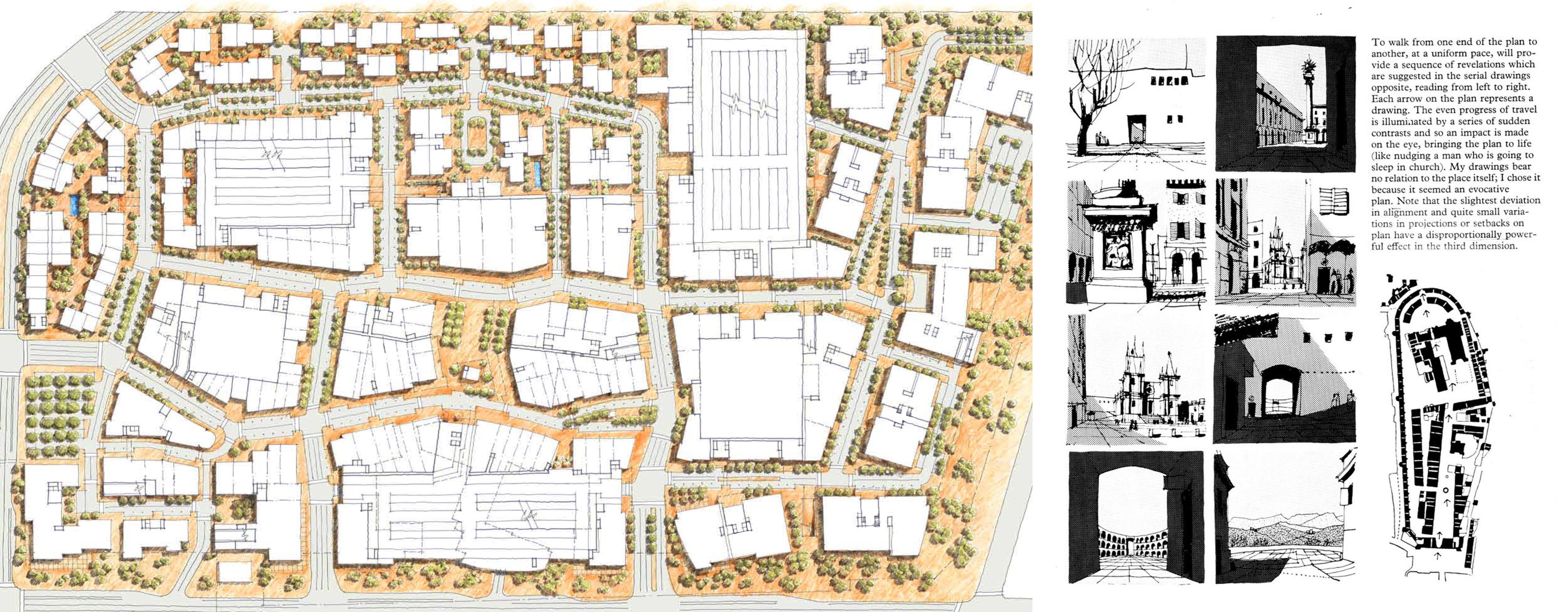

Left: master plan for a mixed-use district in Arizona; right: "serial vision" from Gordon Cullen's seminal "Townscape". The master plan for a new dense, mixed use district on the boundary between Phoenix and Scottsdale formulates a new vision of urbanity based on biophilic design principles. Influenced by the theories and observations of British Urbanist Gordon Cullen, the layout is an evolution of the plan Field Paoli developed for Victoria Gardens, and features a disrupted quasi-orthogonal grid that creates an evolving series of vistas as users move through the project.

In his 1961 classic

"Townscape", British urban theorist Gordon Cullen explored the idea

of how urban environments featuring a sequence of spaces of different scales

created rich and stimulating experiences - unlike the typical orthogonal

street grid that provides a "one size fits all" outdoor space, as

well as endless vistas to nowhere. Dutch urbanist Jan Gehl talks of how

depressing a long urban vista can be - faced with an endless linear street, the

pedestrian is tired even before he embarks on his journey! The experience of walking down long linear streets is reminiscent of the old animated cartoon technique of having a repetitive landscape slide behind a character whose legs are moving, but who is not really getting anywhere. Getting away from linearity and creating more twists and turns makes for a more engaging experience, as in the plan illustrated above for a mixed-use

district in Arizona, which disrupts the grid through the adjustment of street

orientation, by offsetting streets, and through the introduction of a range of

public spaces of different sizes. The streets are experienced as outdoor

rooms rather than endless corridors - places to linger rather than places to

travel through. The project is experienced as a sequence of unfolding vistas

and interconnected outdoor rooms of different scales, transitioning to the semi-private

and private spaces of residences and offices.

This approach contradicts a train of thought that goes something like this: we want our retail-anchored mixed-use destinations to be lively; cities are lively; cities have grids, therefore a grid will create the liveliness of an urban district. But cities aren't lively because they have grids - they're lively because they have people. There is certainly nothing more depressing than a shopping district devoid of people, and by bringing cars into the mix, open air "Main Street" projects such as Easton and Victoria Gardens added some buzz into the heart of the retail, creating more activity and liveliness even during slow times - especially since it doesn't take many shoppers to fill up the limited on-street parking spaces. The danger with this approach however is that the requirements of automobile circulation begin to dictate layout, with traffic engineering rules taking primacy over the pedestrian experience. Easton was visionary in that it used the grid as a planning tool to disrupt the fortress mall; but is it now time to disrupt the grid?

Working and living environments

designed to inspire

Left: Brentford Lock West, London (multiple designers) Right: 1601 Mariposa in San Francisco (by David Baker Architects). These two residential projects, one in London and the other in San Francisco, illustrate a more sensitive approach to medium-density residential planning , with a focus on the quality and "feel" of the spaces in between buildings. Thinking about spaces in between buildings rather than the buildings themselves is a crucial aspect of the design of outdoor retail destinations.

A number of recent residential and office

developments across the globe eschew the rigidity of the grid in order to

create more engaging and resonant public spaces. In London, the Brentford

Lock West project features shifting geometries that create intimate streets and

inviting courtyards; in San Francisco, David Baker Architects' 1601 Mariposa

project is laid out around a gently oscillating central open-air spine.

The Googleplex office campus in Mountain View is like a cellular village,

featuring a grouping of non-linear office buildings. These are bent and arranged to form outdoor courtyards of different scales

in order to encourage physical and mental meandering, in turn fostering

creativity, inspiration and the exchange of ideas. Facebook’s

Gehry-designed MPK 20 building in Menlo Park also features a flowing,

undulating interior layout. These residential and office projects

all go beyond the basics of shelter, safety and functionality, in order to

provide a spatial environment that fosters creativity and inspiration - and they point to a more biophilic approach to site planning and urban design.

Thinking outside the grid

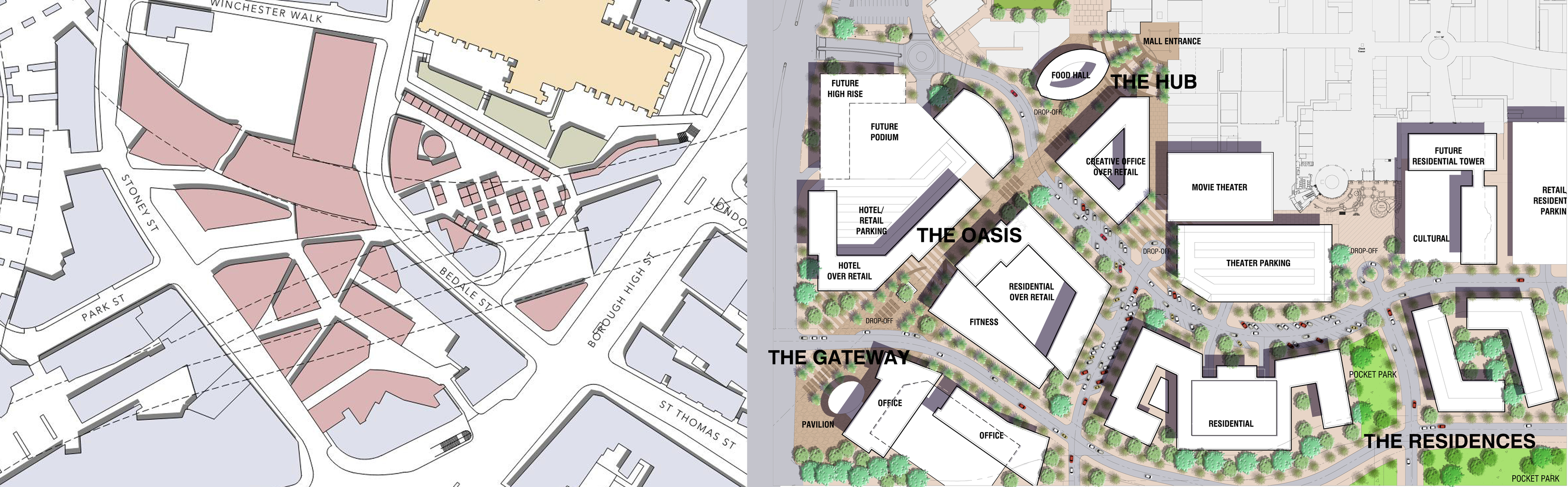

Left: plan of Borough Market, London; right: concept design for a partial mall redevelopment by Field Paoli and Studio T Square. Both layouts appeal to the emotions rather than to reason, engaging the limbic system and releasing anticipatory dopamine through the promise of spatial discovery.

In a similar vein, Borough Market in London is an extraordinarily

lively retail environment - tucked under the arches of two railway viaducts, it

exudes energy and excitement. Walking through Borough is a feast for the

senses, and the informal layout contributes to the place's energy and

spontaneity. From a neural perspective

Borough’s layout combines the cornucopia of foods on display with a sense of

discovery to stimulate the hippocampus (a region of the limbic system

known for memory and prospection), triggering anticipatory release of

dopamine - and according to author and researcher Stephen Asma, from an evolutionary perspective anticipation is the earliest form of imagination . Space and brain resonate to create an intense emotional experience

(the grid on the other hand may trigger neural activity in the neocortex,

an area of the brain more tuned to planning and logic than to emotions). In

the tradition of non-linear projects such as Caruso's Americana at Brand ,

Phase 1 of the Domain, Watters Creek in Allen, TX, One Paseo in San Diego

or Broadway Plaza in the San Francisco Bay Area, the project illustrated on the

right replaces a dark anchor with a disrupted grid layout to

create an informal sequence of varied public spaces that engage user

experience. These projects all foster a sense of discovery, a sense of the

unexpected - and arguably it is our encounters with the unexpected that lead to

transformative experiences. Could these places be more appealing to a

broad swath of today's suburban customers, tenants and renters?

We may look to the convenience of the strip mall or the internet to buy commodities, but when we look for goods and experiences that have a more emotional resonance, or for a place to live and work that can inspire us, we need settings that appeal to our hearts as well as our minds. The term biophilia was coined to reflect the human desire to commune with nature (a desire that lies at the root of the idea of suburbia), and the subtleties of the disrupted grid point to how our built environments could become more biophilic. Disrupting the ubiquitous grid can infuse a place with energy and character, serving the transactional consumer but more importantly inspiring the social customer. Perhaps we can learn from Ralph Waldo Emerson's cows -

- after all, isn't shopping a little bit like grazing?

5 ways to disrupt the grid

- Use focal points to realign streets - a plaza, a major tenant entrance, a civic or community building (Baron Haussmann would approve)

- Create perpendicular intersections at the loop road and use these to generate new alignments

- Emphasize any pre-existing geometries - such as the angled common area of the Aventura Mall

- Create a hierarchy of scales in your street network, from wide to intimate

- Savannah-ize your grid - use pedestrian public spaces to disrupt vehicular circulation