Shoppers enjoying a leisurely stroll at Broadway Plaza, Walnut Creek, CA. Textures, landscaping, generous sidewalks and storefront displays all have a calming effect on the customer’s pace and allow for ample social distancing. (Image credit: Phil Bond)

Walking and Belonging

Walking seems to be the great de-stressor of the current pandemic. Trapped inside during shelter-in-place, we are prone to cabin fever. We all have a need to wander – whether it's going for a walk around the block, hopping in the car to run an errand, or even commuting to work (however much maligned, the daily commute establishes a beneficial physical and psychological distance between the rituals of home and the rituals of the workplace).

We can walk slowly and soak up our surroundings, exploring a new destination or on vacation, and we can walk quickly, either to burn calories and increase our Fitbit count, or because we have somewhere to get to. Walking is not just about getting out of the house: it is about connecting and reconnecting to our surroundings and our community, and reinforcing our sense of belonging.

When any of us go for a walk, we enjoy physical and psychological benefits. Studies have shown that walking makes the heart pump faster, circulating more oxygen to muscles as well as the brain. After a walk, people perform better on tests of memory and attention. Walking on a regular basis also promotes new connections between brain cells, stimulates the growth of neurons and increases the volume of the hippocampus (a brain region crucial for memory and wayfinding).

Going on foot returns us to our first self: it delivers us to the movements of ambling and flowing, which echo the movements of our mind and spirits better than sitting and riding. Walking helps bring out our inner child and stimulates mental wandering: we overlay the world before us with a parade of images from the theater of our minds. This is the kind of mental state that studies have linked to innovative ideas and aha moments – and, more importantly for retailers, it's a mental state that makes us receptive to the seductive charms of consumer goods. Walking lets us loosen up and live a little!

Walking is a physical experience that is both more rewarding and more powerful than anything that could be achieved on-line. During shelter-in-place, as the Wall Street Journal has recently noted, many people are rediscovering how walking can re-establish a strong sense of belonging to their surroundings and their neighborhood. What can mall owners do to take advantage of this?

Walking and the Birth of Shopping

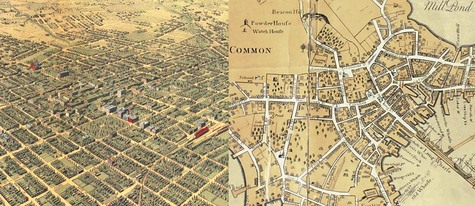

While people may have been going to markets since the dawn of urban civilization, high-end shopping did not emerge until the invention of the glazed arcade in Paris at the beginning of the 18th Century. Sidewalks were not commonplace at the time, and the arcade offered a refuge from the dirt and squalor of the street, a place to meet up with acquaintances to exchange a little gossip, and an opportunity for some window shopping while enjoying a leisurely walk.

Image: The Passage des Princes, Paris, opened in 1860. Storefront displays, glass skylights and gas lighting all contributed to the creation of a setting for promenading and meeting friends - a refuge from the hustle and bustle of the street, and an opportunity to expand social networks.

The Parisian arcade was a completely new kind of environment, designed around a completely new activity: the leisurely social walk. Sky-lit by day and and gaslit by night, the arcades were flanked on both sides by large storefront windows displaying a multitude of finely crafted objects, books, clothes and accessories. But you didn’t go to the arcade because you needed to buy something – you went there to meet your friends, and to enjoy a social stroll with them. Shopping wasn’t about buying; it was above all a social experience that gave definition to the peer group you belonged to. Retail was theater: the storefronts were the stage set, and customers were both actors and audience, seeing and being seen. Interestingly the social customs of the time dictated social distancing (the birth of the shopping arcade happened during a time of cholera epidemics in Europe), and a simple nod of the head or a tip of the hat was the customary way to greet one’s acquaintances.

Walking and the Birth of the Mall

The same desire to "escape" from crowded city streets found a completely new expression about 100 years later with the emergence of the post-war American suburb. Suburbs had one thing in common with 18th century Paris: a noticeable lack of sidewalks. As retail consultant Paco Underhill describes in his book The Call of the Mall, in the suburbs there was no such thing as a stroll down the street to the cleaners or the appliance store or the dress shop, since no place could be easily reached by walking, and even if you did walk (assuming there were sidewalks), you didn’t enjoy any of the happenstance meetings a city stroll afforded.

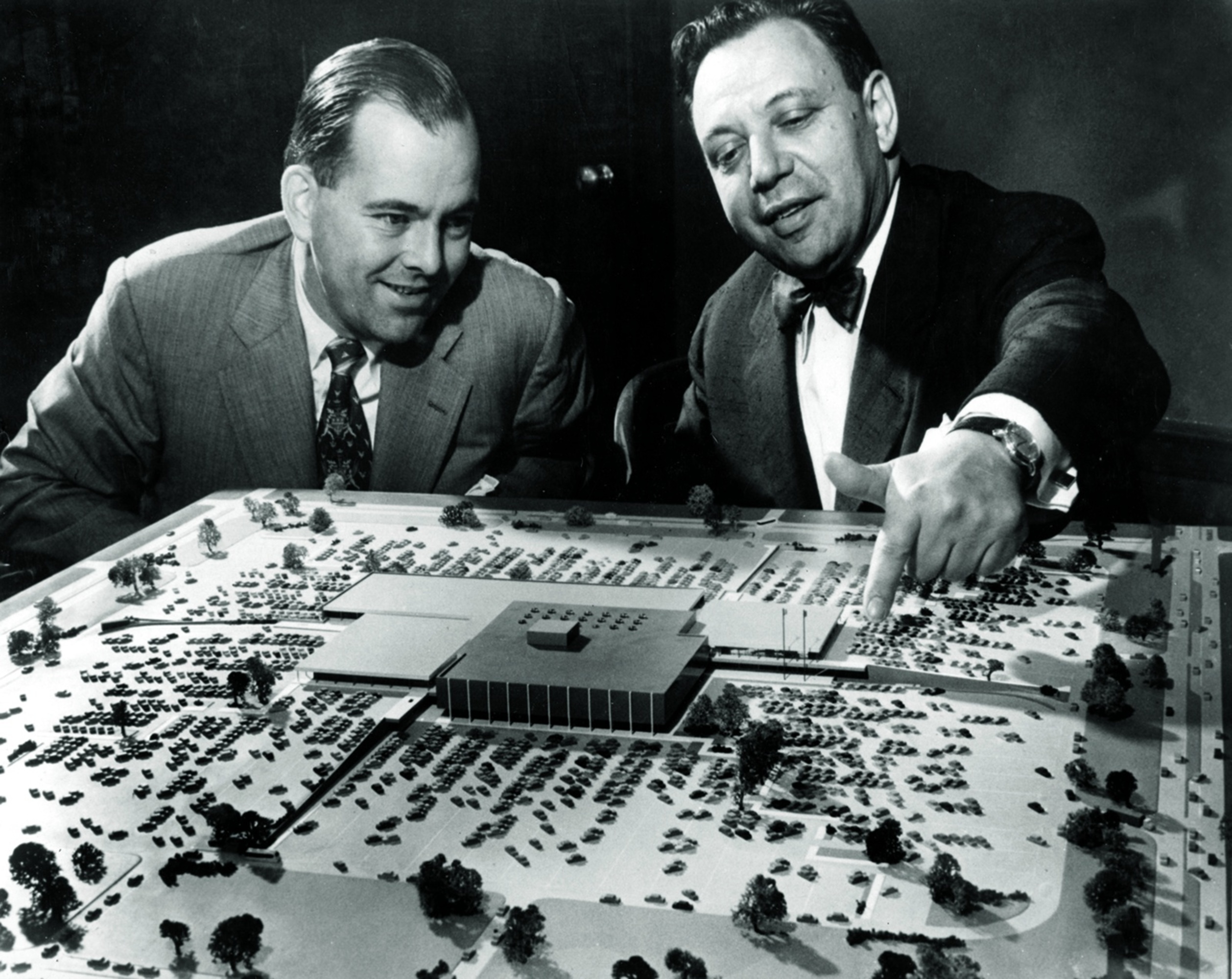

When Minneapolis-based Dayton's Department Store

approached architect Victor Gruen with ideas about opening a new store in suburban

Edina, Gruen immediately saw this as an opportunity to re-introduce a

social destination to suburbia. Gruen wanted to give suburbanites a place

where they could go for a walk, a place they could connect with each other

outside of the home. Southdale was conceived as a cross between the

European town square and the shopping arcade: the mall was as much a social and

leisure destination as it was a shopping destination, and a welcome relief

for the homebound suburban mother. It was to be the centerpiece of a

walkable district that would also include schools, offices and hospitals. The

emphasis on walkability continued throughout Gruen's career, as he reimagined downtowns

as pedestrian enclaves, built around the pleasures of strolling,

window shopping and people watching. Gruen believed that

the built environment would be more meaningful if it was shaped around the

pedestrian experience.

"It's going to feel just like Paris!" Gruen was trying to get people out of their suburban cocoons (the house, the automobile, the office) into a walkable environment in order to foster social interaction.

By the 1980s, however, a great many suburban homemakers who had been able to while away the hours at the local mall had now begun working outside the home, either full-or part-time. This dramatically changed the dynamics of the shopping mall, since time was becoming a rare and precious commodity. Instead of being a leisure destination, the mall needed to focus on convenience and efficiency, migrating into a different mental category: a place to get through the shopping list quickly and efficiently, rather than a place where you could hang out with friends and family and enjoy some leisure time. The mall was becoming a formula, understood by developers, investors, shoppers and retailers alike: a pre-packaged collection of national tenants delivered to the consumer with a high degree of operational efficiency.The problem, however, with designing something around efficiency and convenience is that when something more efficient and convenient comes along, you are going to lose out – and lose out many malls did, initially to big box centers, and eventually to the internet.

Millennials Like to Walk

They say that each generation is shaped by defining moments. For the Millennials it was 9/11, the rise of the internet, and graduating into the great recession; and now we need to add Covid-19, which may be more impactful than all of the above.

Covid is giving denser urban environments a bad name, and may reinforce Millennials’ preference for living in “surbia” – a place with a connected smalltown feel, where goods and services are within walking distance. Millennials are appreciative of the joys and benefits of walking and walkability, of living life in the slow lane, and of integrating leisure time in their everyday life.

The

importance of walkability and leisure time points to a renewed path to

relevance for the traditional shopping mall, and its evolution into mixed-use. Millennials

are looking for a slower environment, one which features places to hang

out, hip tenants and well-designed storefront displays. An environment that

pays attention to their noses as well as their eyes (the smell of leather

coming out to the Shinola store, the smell of freshly ground coffee, the smell

of baked bread); an environment that feels connected to where communities of people

work and live.

Victoria Gardens, Rancho Cucamonga CA: The mall has disappeared and turned into a walkable neighborhood, with wide sidewalks and lush landscaping.

Reinventing the Mall in the Post-Covid Era

Right now, malls and tenants are fighting for survival, with a focus on the safety and convenience of curbside pick-up. But if malls are to endure, owners will need to look beyond this utilitarian approach and leverage the mall’s capacity to bring people together to create fundamental, resonant and relevant experiences.

The birth of shopping was associated with the social walk: the ability to interact with your peers in a welcoming indoor/outdoor setting that promotes relaxation and social interaction. The purchase of goods certainly occurred, but it was within the context of a social experience. That is the strength of the mall today: a physical walk at the mall is going to be a lot more fulfilling than a virtual walk through the pages of Amazon.com.

The mall will need to change in order to accomplish that.

What makes for a memorable walking experience? A mix of familiarity with a dash of the unexpected; opportunities for social interaction and conversation; visual richness and variety; a variety of spatial scales, from grand to intimate; a textured visual environment; enticing food aromas; the gathering of different communities (residential, office), and of course people, people, people. All these elements can combine to create an anticipatory release of dopamine when the customer thinks about a visit to the mall, and all of these experiences can be provided safely and with appropriate distancing.

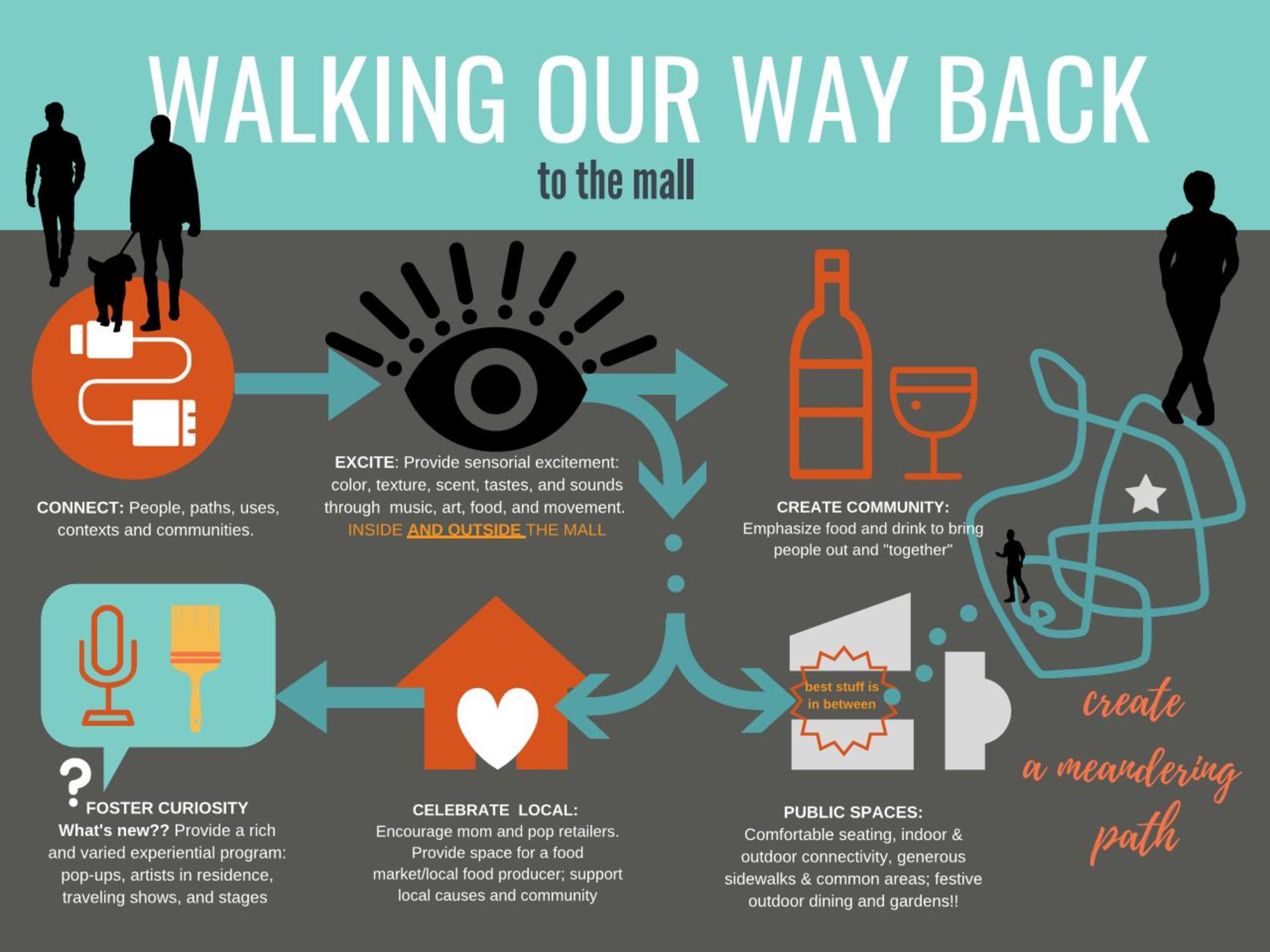

How might these elements be folded into the experience of the typical mall? The retail reset we are going through provides opportunities to implement substantial changes, and the following list is a menu of sorts that represents ways to disrupt the traditional monolithic single-use mall.

Like a walk in the park: moving past Covid-19, the more successful malls will be the ones that go beyond being just a place to buy things. The Patios at Valencia Town Center (image credit: Jim Simmons)

Rediscovering your neighborhood (mall)

As noted in the Wall Street Journal, walking will open your heart to what’s around you. Listed below are some strategies that mall owners and managers can adopt to create the kind of environment that will foster slow, leisurely walks.

Connect visitors to context:

- Introduce meandering paths

- Break up parking/eliminate surface parking lots

- Add communities: office, residential

- Establish “doors open” days at the mall – doors wide open during shoulder season (feel the breeze)

- Make the transition from enclosed to open air

Foster a unique culture at the mall:

- Integrate museum exhibits

- Offer Instagrammable experiences

- Install interactive art – the adult equivalent of the children's playground

- Provide opportunities for education

- Integrate a local library outpost – browsing, programming, teen space; wifi

Provide space for community representation:

- Create spaces for displaying a walk-through community art exhibit or history exhibit

- Celebrate residents who live within walking distance

- Creative office workers

- Display recognition of retail employees

- Food creates community: emphasize bars, restaurants

- Third places

Provide pop-ups & the unexpected:

- Food/local chef restaurant pop-ups

- Retail pop-ups for digitally native brands

- Food carts

- Traveling art exhibits

- A poet in residence

- Fun and games

- Chess players

- Three card monte

- Virtual gaming

Energize the tenant look and feel:

- Allow them to spill out into public space (sandwich boards, seating)

- Encourage mom and pop retailers

- Emphasize creative visual merchandising

- Provide space for a food market/local food producers

- Establish guidelines for well-crafted signage

- Encourage enticing aromas

- Second hand stores

- Surprising tenant adjacencies

Incorporate public spaces:

- Newsstand

- Comfortable seating, gathering, living rooms

- Street furniture

- Sandwich boards

- Indoor/outdoor connectivity

- Generous sidewalks/common areas

- Generously spaced tables in festive outdoor dining gardens

What about the non-traditional mall shopper?

- Hardware store

- Brewery

- Woodshop

- Grill/outdoor cooking

- TV/music

- Knife store/tool sharpening

- Auto parts

- Barbershop

- Entertainment

Beyond retail (see also "culture"):

- Workplace/creative office

- Manufacturing space, handmade goods

- Health clinics

- Day spas

- Personal care

Promote people-watching and the theater of everyday life:

- Family

- Friends

- Neighbors

- Retail employees

- Co-workers

- Strangers

- Tourists