Experiential urban design shapes how our urban environment is perceived and experienced. Its

emergence and evolution as an approach to design can be traced to a tradition

of thinkers who have typically worked outside of the architectural mainstream,

and who have studied urban space in terms of its psychological aspects rather

than its visual and formal appearance. In recent years this approach has been

validated by ongoing research in the ever-expanding field of neuroscience,

deepening our understanding of the many ways in which our urban environment

impacts our moods and behaviors.

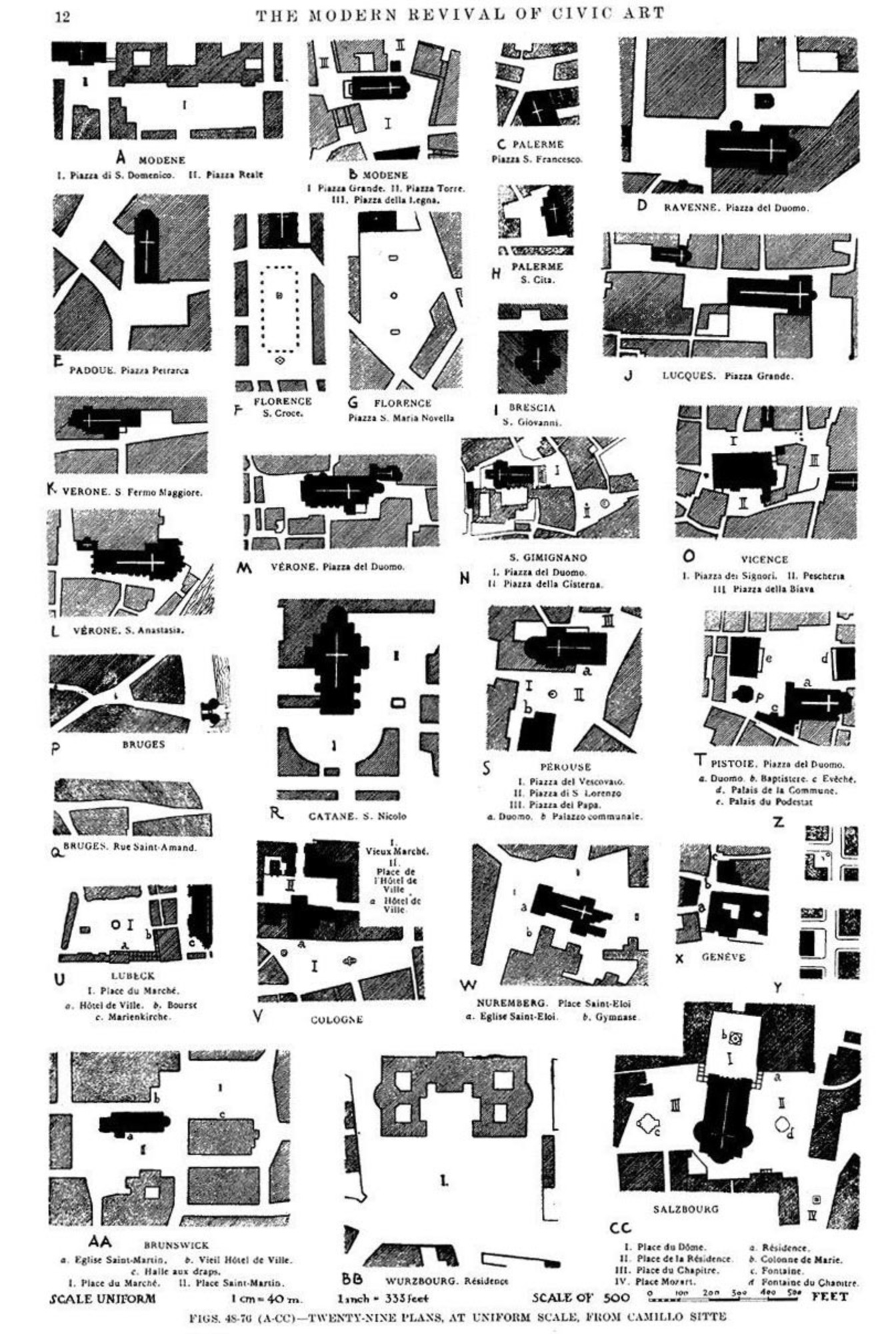

Like many new ideas, experiential urban design has evolved in fits and starts, with a few key publications along the way. One of the pioneers in the field was Camillo Sitte, an architect dismayed by the control exerted by engineers over the emerging field of urban design in the 19th century. After Sitte we fast forward to the end of the 50's, which saw the publication in quick succession of three classic books: Steen Eiler Rasmussen's Experiencing Architecture (1959), Kevin Lynch's The Image of the City (1960), and Gordon Cullen's Townscape (1961).

The seventies gave us placemaking guru Christopher Alexander's magnum opus, A Pattern Language (1977), and from there we jump to the present day and to the emergence of a host of books exploring the relationship between architecture, urban design, and neuroscience, including the very readable Places of the Heart by psychologist Colin Ellard, and Welcome to Your World by architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen. None of these authors are mainstream architects, which is perhaps why they have been able to adopt a viewpoint outside of typical architectural preoccupations with the manipulation of form.

The list below is by no means comprehensive and represents the evolution of an ongoing exploration of the relationship between place and society as seen through an understanding of human experience.

The lost art of urban design: Medieval European public spaces as documented by Sitte.

The lost art of urban design: Medieval European public spaces as documented by Sitte.

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles

(First published in 1889)

Sitte was a Viennese architect and painter active in the second half of the 19th century, when many European cities were undergoing large expansions due to tremendous growth in urban population (the rise of urban manufacturing coupled with the increased mechanization of farming meant that both people and the food they needed for sustenance converged towards urban centers at an unprecedented rate). Sitte bemoaned the fact that these expansions were typically designed by engineers rather than architects and looked to traditional European city form as an alternative model of urban design. He studied the shape and scale of beloved and enduring medieval and public squares, suggesting that their design was as much the result of artistic considerations as it was the result of incremental development over time. He advocated for a humanistic rather than functional viewpoint, with an emphasis on the integration of physical context, and denounced the engineering and planning obsessions with functionality, manifested through the use of rectilinear grids and a one-dimensional focus on traffic circulation.

"Rugged terrain, water courses, and existing roads should not be ruthlessly obliterated for the sake of a stupid rectangularity. On the contrary, they should present welcome occasions for deviating street lines and other informalities. Irregularities of this kind, so often removed at tremendous expense in these days, are absolute necessities. Without them a certain rigidity and cold affectation descends upon even the finest works. Moreover, it is precisely these irregularities that provide easy orientation in the street network."

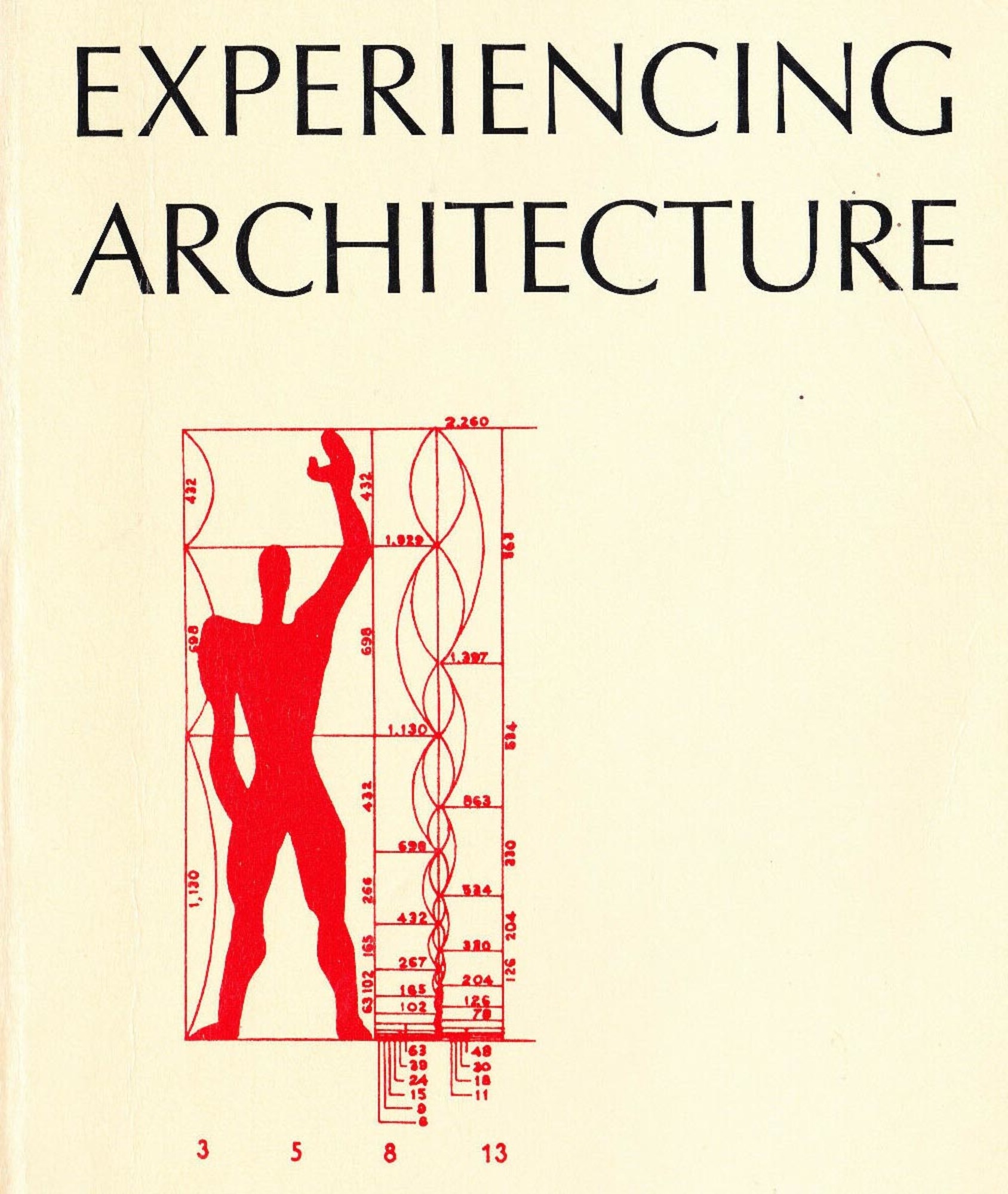

Experiencing Architecture: It’s all about the body

Steen Eiler Rasmussen, Experiencing Architecture

(MIT press, 1959)

Writing at a time when modernism was beginning to lose some of its luster, Rasmussen, a Danish architect and planner, tries to rekindle the relationship between people and buildings, perhaps to counteract the growing alienation felt by many toward the contemporary buildings of the time. In trying to explore the positive ways that buildings and spaces can impact us, he introduces a number of themes that resurface throughout the subsequent literature of experiential urban design: how we are shaped by our environments ("man first puts his stamp on the implements he makes and thereafter the implements exert their influence on man"); how we cannot help imbuing our environments with meaning ("It is a well-known fact that primitive people endow inanimate objects with life. Streams and trees, they believe, are nature spirits that live in communion with them. But even civilized people more or less consciously treat lifeless things as though they were imbued with life"); and how we might even at times become one with our environment ("The person who hears music or watches dancing does none of the physical work himself but in perceiving the performance he experiences the rhythm of it as though it were in his own body. In much the same way you can experience architecture rhythmically—that is, by a process of re-creation"). For Rasmussen the ultimate architectural experience is the experience of choral music inside a church - both building and human body become synchronous instruments bound together by sound, space, light and shade, color and the smell of the censer. Rasmussen argues that this sympathy exists in more modest manifestations throughout our encounters with the built environment, and that designers should constantly remain aware of this.

"We re-create the observed into something intimate and comprehensible. This act of re-creation is often carried out by our identifying ourselves with the object by imagining ourselves in its stead. In such instances our activity is more like that of an actor getting the feel of a role than of an artist creating a picture of something he observes outside himself."

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City

(MIT Press, 1960)

An urban planner teaching at MIT, Kevin Lynch set out to understand how residents perceived their urban environment: how they oriented themselves within it and how they navigated through it. Focusing on the three very different urban cores of Boston, Jersey City and Los Angeles, Lynch conducted wide-ranging interviews to determine the makeup of the typical mental map present in a city dweller's mind. An analysis of the interviews led to his categorization of a "legible" urban fabric into five distinct elements: paths, nodes, landmarks, districts and edges. Remove these, and you end up with "confusions, floating points, weak boundaries, isolations, breaks in continuity, ambiguities, branchings, lacks of character or differentiation" — all conditions leading to a sense of alienation relative to one's surroundings. A recurring feature of Lynch's interviews is the role played by retail shops in acting as key urban markers. Shops bring a building to life by making its street level recognizable, essentially wrenching it out of its potential anonymity and giving it meaning and purpose. In addition to retail shops, Lynch emphasizes the importance of pockets of urban greenery, which inspire visits bypeople going out of their way on their daily commute: "Several reported daily detours which lengthened their trip to work but allowed them to pass by some particular planting, park or body of water." Lynch's work suggests that pathmaking may be as important as placemaking in the creation of relatable urban environments.

"Nothing is experienced by itself, but always in relation to the sequences of events leading up to it, the memory of past experiences."

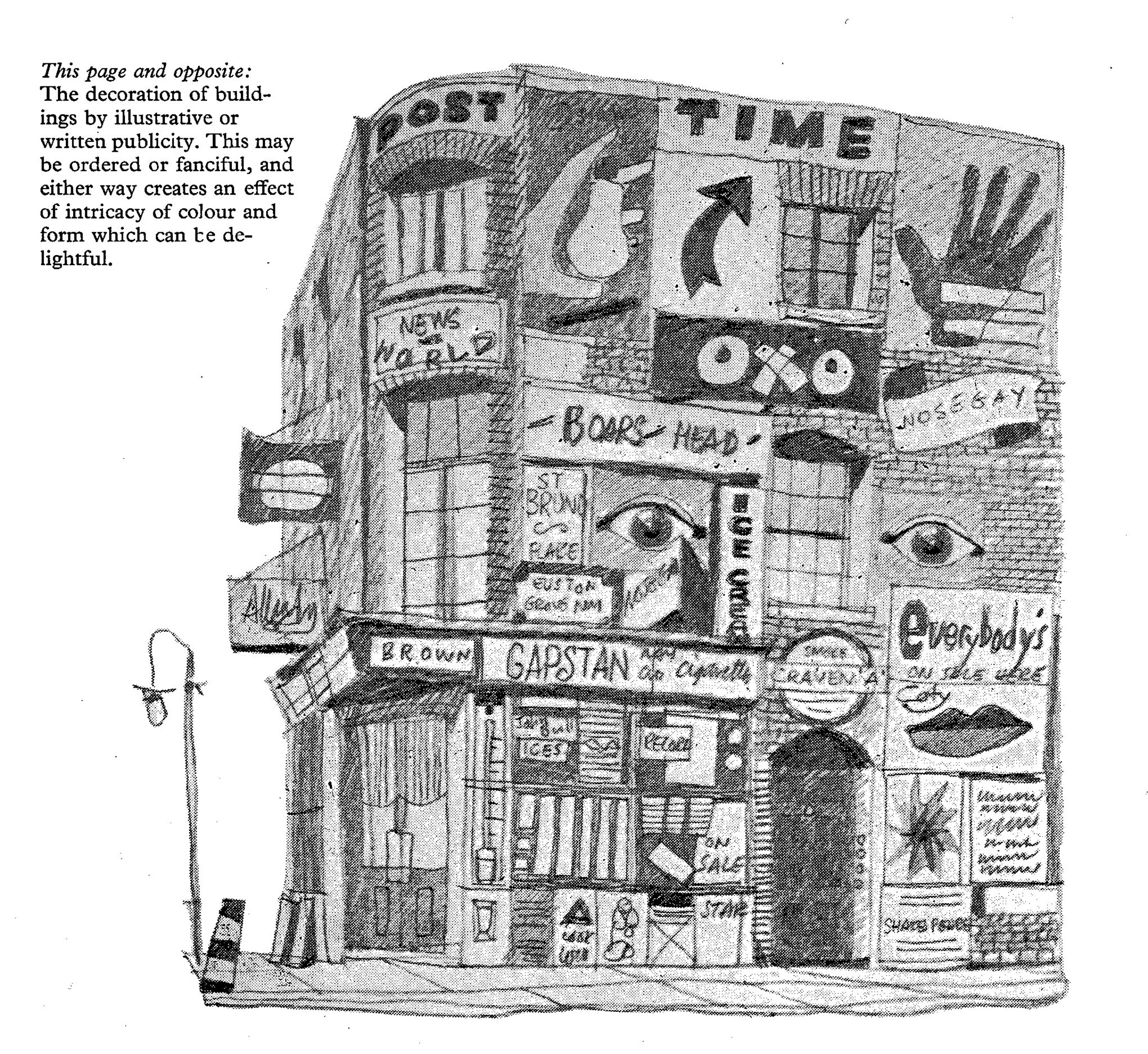

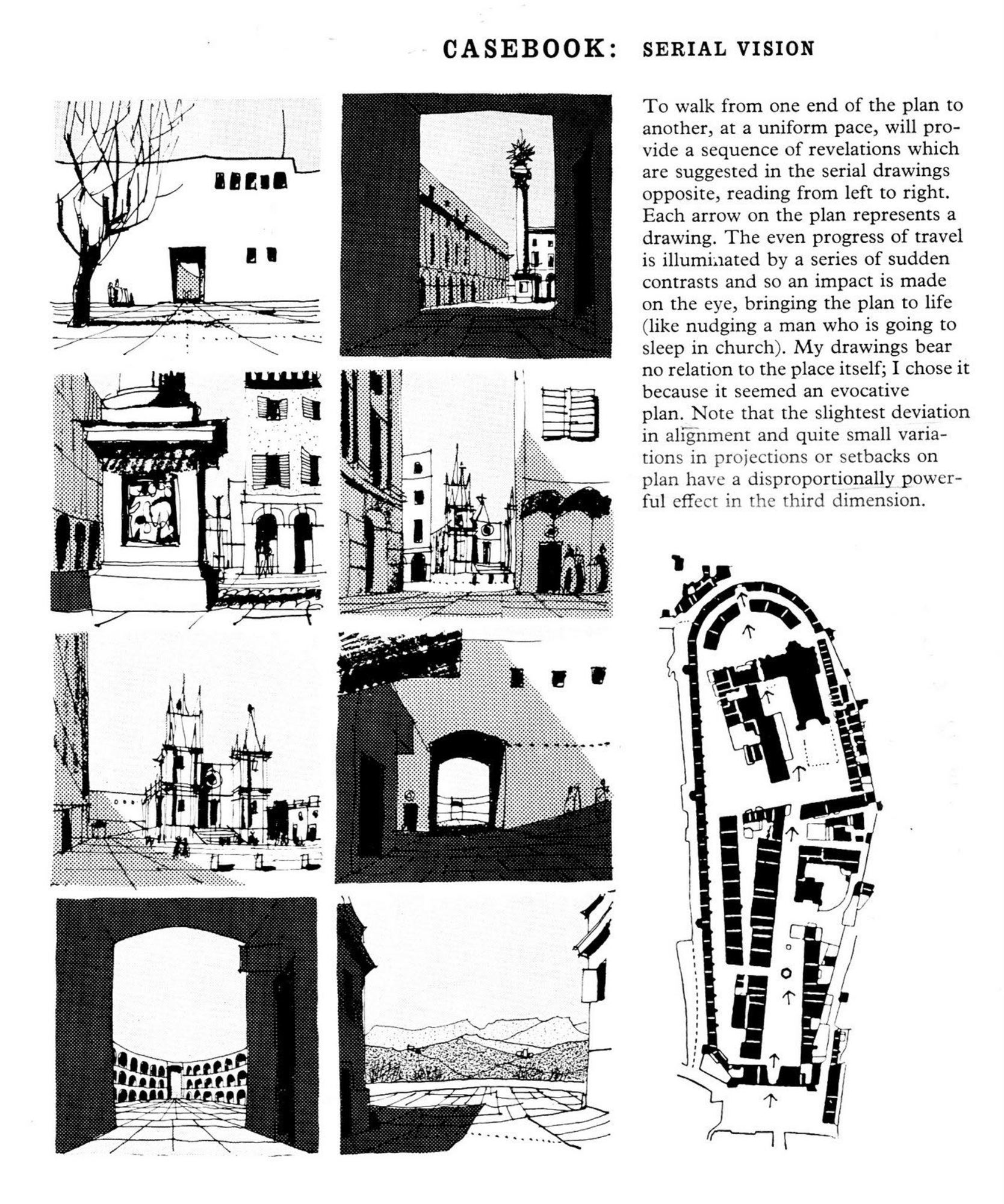

Sketch by Gordon Cullen.

Gordon Cullen, Townscape

(Reinhold Pub. Corp., 1961)

The Concise Townscape

(Routledge, 2012)

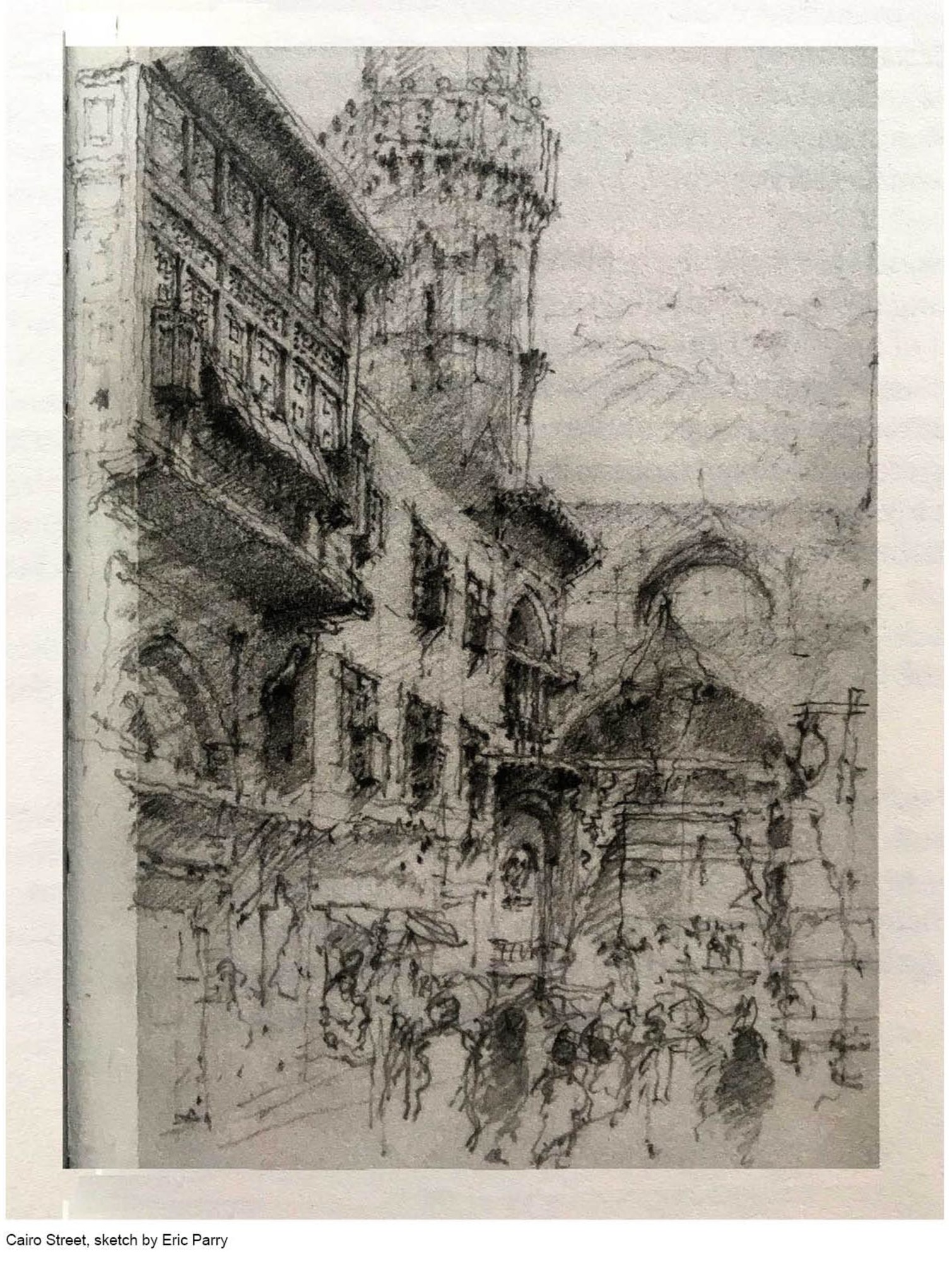

If Lynch's work brought notions of placemaking and wayfinding to the foreground, Gordon Cullen's work goes one step further by cataloging examples of memorable paths and destinations, focusing on their experiential qualities. Trained as an architectural draughtsman, Cullen developed a loose and evocative sketching technique that was to influence many of his contemporaries, including Richard Rogers and Norman Foster, who were both about to embark on their architectural careers. His sketches were notable for highlighting everyday features of the urban environment that were typically ignored in architectural renderings: retail signs, advertisements, street furniture, vehicular signage and people. Cullen became interested in the choreography of all these elements and developed the notion of "serial vision:" the experience of wandering through a sequence of urban settings, and how one setting may set up and reinforce the next. Cullen categorized spatial experiences in an attempt to explain why certain environments resonate with us, in many ways anticipating the more systematic and analytical approach adopted by Christopher Alexander in the following decade.

"The outdoors is not just a display of individual works of architecture like pictures in a gallery, it is an environment for the complete human being, who can claim it either statically or in movement. He demands more than a picture gallery, he demands the drama that can be released all around him from floor, sky, buildings, trees and levels by the art of arrangement."

Christopher Alexander, A Pattern Language

(Oxford University Press, 1977)

Together with its companion book The Timeless Way of Building, A Pattern Language offers a compelling (although at times folksy) interpretation of how our surroundings are structured. At an encyclopedic 1170 pages, this is not a short read, but it is the sort of book you can enjoy by opening a page at random now and then and just diving in. The book is assembled as an architectural and urban design kit of parts, but the parts are human situations and activities rather than architectural or urban fragments. So instead of talking about abstract architectural and urban forms, Alexander talks about promenades, connected play, street cafe, staircase as a stage, garden seats — the list goes on, running to a total of 253 items. Individuals, groups, and families are very much at the heart of Alexander's approach, which is a product both of its time (Cambridge in the late 70's, which still had a pronounced hippie vibe) and Alexander's background in mathematics, hence his urge to classify, number and systematize. Is it overly ambitious to try to assign the same design methodology to the scale of the city ("City Country Fingers," pattern number 3) and that of a building detail ("Half-Inch Trim," pattern number 240)? The answer is yes, but at least Alexander was trying to shake up how the profession approached design, as evidenced through the monolithic "redevelopment" projects taking place in the 70's. Patterns dealing with the scale and life of the street are particularly compelling: “Web of Shopping” (pattern #19), “Promenade” (#31), “Shopping Street” (#32), “Market of Many Shops” (#46), “Street café" (#88), “Corner Grocery” (#89), “Beer Hall” (#90), “Food Stands” (#93) all deal with the life and vitality of retail. Alexander extolls the virtues of a healthy public realm, and the role that retail plays in holding communities together. His examples may harken to a bygone age, but one that seems to be making a comeback as retail malls struggle to remain relevant and customers look for more connected ways to go about their daily lives.

"Throughout history there have been places in the city where people who shared a set of values could go to get in touch with each other. These places have always been like Street theaters: they invite people to watch others, to stroll and to browse, and to linger. In all these places the beauty of the promenade is simply this: people with a shared way of life gather together to rub shoulders and confirm their community."

Aerial view of a Las Vegas suburb: repetition and monotony are bad for your brain!

Colin Ellard: Places of the Heart: The Psychogeography of Everyday Life

(Bellevue Literary Press, 2015)

Neuroscience and architecture are two disciplines that have generated much impenetrable prose, and so it is with legitimate apprehension that one would take on a book dealing with the combination of the two. Ellard, however, a psychologist and director of the Urban Realities Laboratory at the University of Waterloo in Toronto, describes the impact of place on our psyches in an extremely approachable and readable manner. He explores how we are deeply impacted by the settings in which we live, and groups our reactions into five major categories: affection, lust, boredom, anxiety, and awe. Retail environments, for example, are very much part of the "lust" category, and Ellard acknowledges that for many years now retailers have been experts in the dark arts of psychological manipulation through design. The sections on boredom and anxiety deal with the sterility of many urban and suburban environments, and the book includes a study on the psychological impacts of the blank facade of the Whole Foods Market in New York's Bowery district (a grocer may prefer shelf and wall space to a storefront, but does the trade-off make economic sense if you run the risk of making your customers feel anxious rather than joyful as they approach and enter the store?). The sections on affection and awe hint at the disconnect between architects and the public realm: we all go to architecture school to learn how to design awesome/awe inspiring buildings, and that may be appropriate for a church, museum or city hall, but perhaps for the larger part of the built environment (the places where we live, work and shop) the designer's focus should be eliciting affection rather than awe.

"Despite the unfamiliarity of the average city dweller with the grammar and vocabulary of the natural environment, we still possess faint echoes of some deep, primal connection with the kinds of environment that shaped our species. As we shall see, these echoes are written deeply into our bodies and our nervous systems, and they are always at play in shaping our movements through places, our attractions and repulsions from particular locations, our feelings, stress levels, and even the function of our immune systems."

Sarah Williams Goldhagen: Welcome to Your World

(Harper, 2017)

Welcome to Your World feels very much like a wake-up call issued to architects. Goldhagen, an architectural critic for The New Republic and a teacher at the Harvard GSD, takes up some of the themes introduced by Colin Ellard and provides an overview of the latest thinking on how our environments influence our behavior: we get to know the world through our bodies rather than through our minds, and the bulk of our cognitions are nonconscious and associative in nature. The environment therefore impacts us in ways that we don't even perceive: for example, a room with a tall ceiling will foster creative thinking. Going beyond the influence that buildings and spaces have on individuals, Goldhagen examines how the urban environment impacts social behavior, looking at neighborhoods in Paris, Jerusalem, and Seoul to explore the relationship between place and culture. Our minds mirror our settings. If we operate in a richly layered environment, our minds will inevitably soak in, reflect and absorb the qualities of that environment. Goldhagen challenges designers to figure out how to create these kinds of environments.

"Because of the memories we form in such settings and then recall and rely upon for the rest of our lives, they literally create the framework whereby we define and conceive of who we are. Enriched environments, whether attention-focusing or attention-restoring, whether awe-inspiring, defamiliarizing, or plainly comforting, will always be the habitats best suited to the human project of personal, familial, and communal well-being, self-actualization, and accomplishment.”

Experiencing the City in motion: Gordon Cullen’s serial vision.

Experiencing the City in motion: Gordon Cullen’s serial vision.

And a few more....

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (1964)

- Edmund N. Bacon, The Design of Cities (1967)

- Bernard Rudowsky, Streets for People (1969)

- Yi Fu Tuan, Space and Place, the Perspective of Experience (1981)

- William Whyte, City: Rediscovering the Center (1988)

- Richard Sennett: The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities (1992)

- Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (Academy, 1995)

These are all authors who have contributed to the evolution of a different way of looking at the built environment — one focused on how it is experienced rather than how it is designed. Although Architecture with a capital A has an important role to play in the structuring of our environments, the authors mentioned above all suggest that an exploration of the "in between" (the spaces between buildings and the paths that connect them) is more critical to the creation of a successful public realm.